Gifts

Shout-out to the Legion of Super-Bloggers' fearless leader Little Russell Burbage who sent me two Sta Trek-related Little Golden Books out of the blue, I Am Captain Kirk and I Am Mr. Spock. Neat art!

"Accomplishments"

At home: It is perhaps astounding that Trainspotting, a film dripping in Scottish argot, based on an Irvine Welsh novel (not an obvious adaptation), about heroin addicts, would become a hit, but there it is. It isn't just a tent pole of 90s pop culture, but made stars out of Ewan McGregor, Kelly Macdonald, and director Danny Boyle, whose fearless visual style managed to capture Welsh's metaphors while still allowing the raw truth of addiction to be depicted. McGregor rummaging around the Worst Toilet in Scotland cannot be deleted from memory. A large part of the appeal is the soundtrack, which is perhaps better remembered than the film itself (something it shares with Garden State, I think), but that's definitely not the only thing going for it. Though all the characters are screw-ups of the highest order, all but Begbie (let's call him the villain) are sympathetic, and we're well happy to spend a couple of hours listening to McGregor's rendition of Welsh's acid narration as their comedies and tragedies play out.

They say you can't go home again, but T2 Trainspotting manages it. It can't be the icon the original film was - that's really a matter of time and generation - but it's fun catching up with the crew 20 years on (yes, they somehow survived). Definitely of a piece with the original, it has Boyle trying lots of visual tricks, a good balance of comedy and drama, at least one early disgusting moment, a similar musical vibe, and revisits the sins of the first film. It has its own story to tell, about recovery, the power of addiction, and forgiveness, but I think just the right amount of call backs to make old fans smile right to the end. I might have to watch myself lest I start singing that "1690" song (from the BlackKklansman sequence). And if you're afraid it's all going to end in the bleakest of ways - because SUBJECT MATTER - I can assure you it doesn't, though you'll have a lot of scares along the way.

Let's make it a trilogy, shall we? Filth is, like Trainspotting, an Irvine Welsh novel adaptation, and it seems Trainspotting is the template for how you should carry an Irvine Welsh novel to the big screen. Hallucinatory moments, savagely funny voice-over, fast-paced editing, the whole lot. Unlike Trainspotting, the lead character isn't all that sympathetic though. James McAvoy plays Bruce Roberston, a corrupt Edinburgh cop who cares more about his promotion than solving crimes, but his ambitions might be waylaid by a mental breakdown. McAvoy is well supported by a cast full of recognizable faces (even when a character doesn't actually have lines), most prominently Jim Broadbent* as a psychiatrist with a giant cranium, Imogen Poots as maybe the only good person on the police force, John Sessions as the restrained but bigoted boss, Shirley Henderson as the victim of Bruce's dirty phone calls, and Downton's Joanne Froggatt as perhaps the only purity in his life. So it's unfortunate that the movie doesn't always work. The ending is messy. And lot of the visual inventiveness comes from images that seem random (unless you read the book, presumably). I like many of the moments - as dark and offensive as it gets at times - but the adaptation from the novel could have used a bit more work.

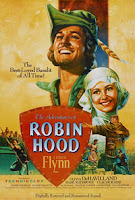

It was interesting watching Michael Curtiz's The Adventures of Robin Hood with people essentially raised on Mel Brooks' Men in Tights because it seemed more like an archaeological artifact to them. So much of that movie is taken from Adventures that it's almost a remake with more jokes rather than a parody or spoof. Anyway, the 1938 classic is like a storybook come to life - it gives you all the story beats you know, has Robin Hood laughing in what you could call camp acting, and is almost impossibly colorful. None of the gritty realism they try to do these days. There's still a high body count in the first act, but it's a bloodless affair. Errol Flynn has a lot of fun, it shows, and there's plenty of swashbuckling action to keep one entertained as we go from set piece to set piece. It's interesting that the Sheriff of Nottingham is sidelined in favor of the more sinister Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone, we're in good hands), though I could use a taller Little John. The most influential Robin Hood movie in film history, but it may seem a little shallow to modern eyes.

I almost saw Bicycle Thieves in a Film History class, but I was exhausted that day (college life) and slept through it. Not a comment on the film, I had my head on the desk before the first five minutes. So I was happy to finally see it this week, though it's really one of those pieces of cinema that's been quoted several times over the years (most recently - and extensively - in an episode of Master of None). Like its namesake, Bicycle Thieves creeps up on you. It shows you systemic poverty in post-war Italy, with characters struggling for subsistence but still giving in to costly temptation. And you're fine. It evokes deep poignant ironies like the need for a bicycle to get a job but money to get a bicycle, and the victim turning thief as one might expect. And you're fine. It has a great relationship between father and son (non-actors both, which seems incredible given their performances) and you're still fine. Or so you think. In the last few minutes, it all hits you, not in what is said, but what is left unsaid. The thieves have taken this man's bicycle, and with it his livelihood, and finally, his dignity. And if you don't feel for him, you feel for his son, sole true witness to the unraveling of his father. And suddenly, I'm not fine anymore. FAVORITE OF THE WEEK

Truffaut's Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows) is cousin to his early short film Les Miston (The Brats), similarly semi-autobiographical and about young boys misbehaving. And it's incredibly well-observed and truthful in its depiction of young people, and how they might bear the brunt of the generation gap. Antoine is on the young side of adolescence, disinterested in school, prone to truancy, and at home, an annoyance to his parents. Without ever glorifying his behavior, the film puts us on his side as he interacts with uncaring authority figures at school, home and the justice system. This may be the first and best film about systemic ageism (seniors like to think ageism victimizes them, but having worked with youth groups for decades, I can tell you young people get it as bad or worse). Every kid has felt the adult world's unfairness, but as they grow up and become unfair themselves, they tend to forget how it used to be. Truffaut doesn't and does his best to remind us. A note on the title: In French (and this isn't an expression I've ever heard in Canada), "les 400 coups" is part of an expression that means "raising hell", but it's also a pun implying "blows" or "knocks", all the things beating Antoine down (and yet not corporeal punishment, which would have muddied the point). The English title gets the pun, but doesn't rotate back to the "mischief" meaning of "coups".

One of the few books I remember reading off my dad's shelf when I was a kid was James Clavell's King Rat, based on the author's own POW experiences in the South Pacific. It makes an engaging film, with George Segal as the title character, an enterprising prisoner who essentially runs the camp through capitalist ventures and scheming, rank be damned. It's hard not to admire King's ingenuity, but there's a cold, pragmatic callousness to him as well, and under the surface, there's an indictment of the Western way of life for which the soldiers have fought for. Corruption of ideals. False friendships (though there's an ambiguity to King's final rejection - he might be freeing his friend from an actionable association). Cruel manipulation. The novel ended with rats eating each other, after all. The film belies its 1965 release date with its setting and (often gorgeous) black and white, so I think they could have gotten away with that final image. They instead go with something more actorly, which is fine.

Operation Crossbow's best idea is to give Sophia Loren top billing despite her not being in the movie very much - I'll let you find out why. Otherwise, it's a bit of a Frankenstein's monster. The first act feels like a slow procedural, setting up a mission to destroy WWII Germany's rocket program by taking it at least three steps before a normal "special ops" movie would. It also means at least half the movie is in German, for realism's sake. I'm happy to see women play important roles on both sides of the conflict however. The second act is the best. Things finally get going and there's plenty of Mission: Impossible type tension as things start to go wrong, with unexpected results. The third act feels more like standard movie fare, with lots of gunfire, explosions and a ticking clock. There are really three different movies hidden in there. Operation Crossbow needed to settle down and pick one of them.

The Caine Mutiny gives you a lot of context before getting to the heart of its subject matter, so by the time Bogart's Captain Queeg rows in, you're familiar with ship personnel and operations, and you've experienced more than just his command style. He's a tragic figure as well as a villain, but the film maintains an ambiguity about his competence that perhaps reflects your own relationship to authority. By the time we get to the third act, we've probably chosen a side, and we'd be punching the air along with the other characters the same way we might have in A Few Good Men during the JAG sequence. But that's not the final word, is it? The climax resolves a bit after that, giving the characters - and the audience that was, in a way, part of the plot - much more to think about. Things are not so cut and dried as they might be in a more formulaic movie. What attitude do we take in the epilogue, knowing what we now know? I've seen the influence this film has had on a lot of stories put to the screen since (including a couple of standout Star Trek episodes), but it takes nothing away from the original. If it doesn't get a perfect score, it's that the romantic subplot is totally surplus to requirements.

I've seen a number of Gene Kelly movies at this point, and I'm always impressed by his physical prowess, but do all his characters have to be jackasses? I'm often wondering if that's him, his type-casting, what the era considered to be a leading man, or what. And yet, he always finds a way to redeem himself by the end. He's the cad that only needs the love of a good woman, and he'll mend his ways. Maybe I've just answered my own question. That's a fantasy for at least some women. I may also be exaggerating, but Anchors Aweigh is certainly in that mold, and worse than most. It's a bit too long for a sailors-on-leave musical, with many sequences you could cut without affecting the story structurally or emotionally. But could we really lose the first ever live action-cartoon integration scene in cinema history? (Oh, and Tom and Jerry?! I didn't expect celebrity toons! And wow, Jerry's a real good dancer too!) I guess it also takes time to give Kelly a proper ethical out to go after his buddy's girl (Frank Sinatra was never so thin nor so timid). Bonus Dean Stockwell as a kid; that's so weird.

Dr. Seuss wrote a live action musical that was made in 1953 - The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T. It's quite something. The movie takes a sort of Wizard of Oz approach, with young Bart having a nightmare about his tyrannical piano teacher, translating him, his mom, and the plumber/mom's romantic interest into a fantasy world the likes of which Seuss may well have drawn. It's entirely loopy and the songs aren't half-bad. Some of them even have Seuss' trademark nonsense rhymes. Those two roller skaters who share one beard are definitely a Seussism. The very best sequence, for me, was the basement dungeon number where the non-pianists have improvised all manner of instrument. It's amazing. Bottom line: A fun, colorful all-ages fantasy filled with dream logic and tapping into something you don't need to be a child to get. Anything that's a chore is a drag, man!

Blithe Spirit, based on a Noel Coward play, is more or less a four-hander in which Rex Harrison's stiff upper lip is unmoved by the arrival of his dead wife's ghost after a catastrophic seance. Thing is, he's remarried, and the ladies don't really get along. I'm really not to sure about Kay Hammond's green make-up as the ghost, or her drunken slur, for that matter, but you get used to these conventions. Despite the macabre streak in the story, it's all quite amusing (and saucy! they couldn't say THAT in an American film of the time!), and it only gets in trouble when it overdoes it. The Margaret Rutherford's muscled medium is quite kooky, but I find a lot of her physical business a bit trying. Similarly, while I enjoyed the crazy (if not entirely unexpected) turns the film took in the third act, there's an awful sense by that point that wit has entirely replaced emotion, and it's hard to care when no one onscreen seems to. Fun, but not entirely successful.

I'm not sure Poltergeist knows what poltergeist are, but that's not my main gripe with the 1982 horror classic (great title, if anything). What bugs me is that it looks great, is well shot for creepiness, and its iconic status in pop culture can't be disputed, but frustratingly, I can't give it a favorable review. For one thing, it treats the supernatural in the same way Close Encounters treats UFOlogy (note Spielberg's hands on approach to producing this thing). The ghosts are essentially extra-dimensional aliens, and the epileptic strobing could be right out of an alien encounter movie (compare it to E.T., for example). Which is fine. Horror tropes reexamined through the lens of science-fiction. But after what normally would be the climax, there's an extra reel, and that one IS from a straight horror film. It was aliens from the beyond, and now it's Indian burial ground revenants, and who the heck knows anymore? It's a little like the idea that you'd call in a psychic investigator, and later, you'd call in ANOTHER psychic expert - isn't that really the same role? - who contradicts the first one, but not really... Was that all a manifestation of the struggle between director Tobe Hooper and his overlord?

Shout-out to the Legion of Super-Bloggers' fearless leader Little Russell Burbage who sent me two Sta Trek-related Little Golden Books out of the blue, I Am Captain Kirk and I Am Mr. Spock. Neat art!

"Accomplishments"

At home: It is perhaps astounding that Trainspotting, a film dripping in Scottish argot, based on an Irvine Welsh novel (not an obvious adaptation), about heroin addicts, would become a hit, but there it is. It isn't just a tent pole of 90s pop culture, but made stars out of Ewan McGregor, Kelly Macdonald, and director Danny Boyle, whose fearless visual style managed to capture Welsh's metaphors while still allowing the raw truth of addiction to be depicted. McGregor rummaging around the Worst Toilet in Scotland cannot be deleted from memory. A large part of the appeal is the soundtrack, which is perhaps better remembered than the film itself (something it shares with Garden State, I think), but that's definitely not the only thing going for it. Though all the characters are screw-ups of the highest order, all but Begbie (let's call him the villain) are sympathetic, and we're well happy to spend a couple of hours listening to McGregor's rendition of Welsh's acid narration as their comedies and tragedies play out.

They say you can't go home again, but T2 Trainspotting manages it. It can't be the icon the original film was - that's really a matter of time and generation - but it's fun catching up with the crew 20 years on (yes, they somehow survived). Definitely of a piece with the original, it has Boyle trying lots of visual tricks, a good balance of comedy and drama, at least one early disgusting moment, a similar musical vibe, and revisits the sins of the first film. It has its own story to tell, about recovery, the power of addiction, and forgiveness, but I think just the right amount of call backs to make old fans smile right to the end. I might have to watch myself lest I start singing that "1690" song (from the BlackKklansman sequence). And if you're afraid it's all going to end in the bleakest of ways - because SUBJECT MATTER - I can assure you it doesn't, though you'll have a lot of scares along the way.

Let's make it a trilogy, shall we? Filth is, like Trainspotting, an Irvine Welsh novel adaptation, and it seems Trainspotting is the template for how you should carry an Irvine Welsh novel to the big screen. Hallucinatory moments, savagely funny voice-over, fast-paced editing, the whole lot. Unlike Trainspotting, the lead character isn't all that sympathetic though. James McAvoy plays Bruce Roberston, a corrupt Edinburgh cop who cares more about his promotion than solving crimes, but his ambitions might be waylaid by a mental breakdown. McAvoy is well supported by a cast full of recognizable faces (even when a character doesn't actually have lines), most prominently Jim Broadbent* as a psychiatrist with a giant cranium, Imogen Poots as maybe the only good person on the police force, John Sessions as the restrained but bigoted boss, Shirley Henderson as the victim of Bruce's dirty phone calls, and Downton's Joanne Froggatt as perhaps the only purity in his life. So it's unfortunate that the movie doesn't always work. The ending is messy. And lot of the visual inventiveness comes from images that seem random (unless you read the book, presumably). I like many of the moments - as dark and offensive as it gets at times - but the adaptation from the novel could have used a bit more work.

It was interesting watching Michael Curtiz's The Adventures of Robin Hood with people essentially raised on Mel Brooks' Men in Tights because it seemed more like an archaeological artifact to them. So much of that movie is taken from Adventures that it's almost a remake with more jokes rather than a parody or spoof. Anyway, the 1938 classic is like a storybook come to life - it gives you all the story beats you know, has Robin Hood laughing in what you could call camp acting, and is almost impossibly colorful. None of the gritty realism they try to do these days. There's still a high body count in the first act, but it's a bloodless affair. Errol Flynn has a lot of fun, it shows, and there's plenty of swashbuckling action to keep one entertained as we go from set piece to set piece. It's interesting that the Sheriff of Nottingham is sidelined in favor of the more sinister Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone, we're in good hands), though I could use a taller Little John. The most influential Robin Hood movie in film history, but it may seem a little shallow to modern eyes.

I almost saw Bicycle Thieves in a Film History class, but I was exhausted that day (college life) and slept through it. Not a comment on the film, I had my head on the desk before the first five minutes. So I was happy to finally see it this week, though it's really one of those pieces of cinema that's been quoted several times over the years (most recently - and extensively - in an episode of Master of None). Like its namesake, Bicycle Thieves creeps up on you. It shows you systemic poverty in post-war Italy, with characters struggling for subsistence but still giving in to costly temptation. And you're fine. It evokes deep poignant ironies like the need for a bicycle to get a job but money to get a bicycle, and the victim turning thief as one might expect. And you're fine. It has a great relationship between father and son (non-actors both, which seems incredible given their performances) and you're still fine. Or so you think. In the last few minutes, it all hits you, not in what is said, but what is left unsaid. The thieves have taken this man's bicycle, and with it his livelihood, and finally, his dignity. And if you don't feel for him, you feel for his son, sole true witness to the unraveling of his father. And suddenly, I'm not fine anymore. FAVORITE OF THE WEEK

Truffaut's Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows) is cousin to his early short film Les Miston (The Brats), similarly semi-autobiographical and about young boys misbehaving. And it's incredibly well-observed and truthful in its depiction of young people, and how they might bear the brunt of the generation gap. Antoine is on the young side of adolescence, disinterested in school, prone to truancy, and at home, an annoyance to his parents. Without ever glorifying his behavior, the film puts us on his side as he interacts with uncaring authority figures at school, home and the justice system. This may be the first and best film about systemic ageism (seniors like to think ageism victimizes them, but having worked with youth groups for decades, I can tell you young people get it as bad or worse). Every kid has felt the adult world's unfairness, but as they grow up and become unfair themselves, they tend to forget how it used to be. Truffaut doesn't and does his best to remind us. A note on the title: In French (and this isn't an expression I've ever heard in Canada), "les 400 coups" is part of an expression that means "raising hell", but it's also a pun implying "blows" or "knocks", all the things beating Antoine down (and yet not corporeal punishment, which would have muddied the point). The English title gets the pun, but doesn't rotate back to the "mischief" meaning of "coups".

One of the few books I remember reading off my dad's shelf when I was a kid was James Clavell's King Rat, based on the author's own POW experiences in the South Pacific. It makes an engaging film, with George Segal as the title character, an enterprising prisoner who essentially runs the camp through capitalist ventures and scheming, rank be damned. It's hard not to admire King's ingenuity, but there's a cold, pragmatic callousness to him as well, and under the surface, there's an indictment of the Western way of life for which the soldiers have fought for. Corruption of ideals. False friendships (though there's an ambiguity to King's final rejection - he might be freeing his friend from an actionable association). Cruel manipulation. The novel ended with rats eating each other, after all. The film belies its 1965 release date with its setting and (often gorgeous) black and white, so I think they could have gotten away with that final image. They instead go with something more actorly, which is fine.

Operation Crossbow's best idea is to give Sophia Loren top billing despite her not being in the movie very much - I'll let you find out why. Otherwise, it's a bit of a Frankenstein's monster. The first act feels like a slow procedural, setting up a mission to destroy WWII Germany's rocket program by taking it at least three steps before a normal "special ops" movie would. It also means at least half the movie is in German, for realism's sake. I'm happy to see women play important roles on both sides of the conflict however. The second act is the best. Things finally get going and there's plenty of Mission: Impossible type tension as things start to go wrong, with unexpected results. The third act feels more like standard movie fare, with lots of gunfire, explosions and a ticking clock. There are really three different movies hidden in there. Operation Crossbow needed to settle down and pick one of them.

The Caine Mutiny gives you a lot of context before getting to the heart of its subject matter, so by the time Bogart's Captain Queeg rows in, you're familiar with ship personnel and operations, and you've experienced more than just his command style. He's a tragic figure as well as a villain, but the film maintains an ambiguity about his competence that perhaps reflects your own relationship to authority. By the time we get to the third act, we've probably chosen a side, and we'd be punching the air along with the other characters the same way we might have in A Few Good Men during the JAG sequence. But that's not the final word, is it? The climax resolves a bit after that, giving the characters - and the audience that was, in a way, part of the plot - much more to think about. Things are not so cut and dried as they might be in a more formulaic movie. What attitude do we take in the epilogue, knowing what we now know? I've seen the influence this film has had on a lot of stories put to the screen since (including a couple of standout Star Trek episodes), but it takes nothing away from the original. If it doesn't get a perfect score, it's that the romantic subplot is totally surplus to requirements.

I've seen a number of Gene Kelly movies at this point, and I'm always impressed by his physical prowess, but do all his characters have to be jackasses? I'm often wondering if that's him, his type-casting, what the era considered to be a leading man, or what. And yet, he always finds a way to redeem himself by the end. He's the cad that only needs the love of a good woman, and he'll mend his ways. Maybe I've just answered my own question. That's a fantasy for at least some women. I may also be exaggerating, but Anchors Aweigh is certainly in that mold, and worse than most. It's a bit too long for a sailors-on-leave musical, with many sequences you could cut without affecting the story structurally or emotionally. But could we really lose the first ever live action-cartoon integration scene in cinema history? (Oh, and Tom and Jerry?! I didn't expect celebrity toons! And wow, Jerry's a real good dancer too!) I guess it also takes time to give Kelly a proper ethical out to go after his buddy's girl (Frank Sinatra was never so thin nor so timid). Bonus Dean Stockwell as a kid; that's so weird.

Dr. Seuss wrote a live action musical that was made in 1953 - The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T. It's quite something. The movie takes a sort of Wizard of Oz approach, with young Bart having a nightmare about his tyrannical piano teacher, translating him, his mom, and the plumber/mom's romantic interest into a fantasy world the likes of which Seuss may well have drawn. It's entirely loopy and the songs aren't half-bad. Some of them even have Seuss' trademark nonsense rhymes. Those two roller skaters who share one beard are definitely a Seussism. The very best sequence, for me, was the basement dungeon number where the non-pianists have improvised all manner of instrument. It's amazing. Bottom line: A fun, colorful all-ages fantasy filled with dream logic and tapping into something you don't need to be a child to get. Anything that's a chore is a drag, man!

Blithe Spirit, based on a Noel Coward play, is more or less a four-hander in which Rex Harrison's stiff upper lip is unmoved by the arrival of his dead wife's ghost after a catastrophic seance. Thing is, he's remarried, and the ladies don't really get along. I'm really not to sure about Kay Hammond's green make-up as the ghost, or her drunken slur, for that matter, but you get used to these conventions. Despite the macabre streak in the story, it's all quite amusing (and saucy! they couldn't say THAT in an American film of the time!), and it only gets in trouble when it overdoes it. The Margaret Rutherford's muscled medium is quite kooky, but I find a lot of her physical business a bit trying. Similarly, while I enjoyed the crazy (if not entirely unexpected) turns the film took in the third act, there's an awful sense by that point that wit has entirely replaced emotion, and it's hard to care when no one onscreen seems to. Fun, but not entirely successful.

I'm not sure Poltergeist knows what poltergeist are, but that's not my main gripe with the 1982 horror classic (great title, if anything). What bugs me is that it looks great, is well shot for creepiness, and its iconic status in pop culture can't be disputed, but frustratingly, I can't give it a favorable review. For one thing, it treats the supernatural in the same way Close Encounters treats UFOlogy (note Spielberg's hands on approach to producing this thing). The ghosts are essentially extra-dimensional aliens, and the epileptic strobing could be right out of an alien encounter movie (compare it to E.T., for example). Which is fine. Horror tropes reexamined through the lens of science-fiction. But after what normally would be the climax, there's an extra reel, and that one IS from a straight horror film. It was aliens from the beyond, and now it's Indian burial ground revenants, and who the heck knows anymore? It's a little like the idea that you'd call in a psychic investigator, and later, you'd call in ANOTHER psychic expert - isn't that really the same role? - who contradicts the first one, but not really... Was that all a manifestation of the struggle between director Tobe Hooper and his overlord?

Comments