"Accomplishments"

At home: One would be completely within one's rights to ask if, by 2019, the world needed any more zombie films. Well, if Little Monsters is going to be the gauge, I'll gladly let another one squeak in. For the second time in 2019, Lupita Nyong'o stars in a horror film, and like Us, the Australian-made Little Monsters starts out as a simple comedy I would have happily watched to the end without anything horrific happening. Nyong'o is simply resplendent as a kindergarten teacher who fiercely defends her class (their lives but also their innocence) from the monsters, and might also help a man-child (Alexander England) grow up in the process. Josh Gad co-stars as the worst children's show host of all time. The kids are universally terrific and feel real. Despite the coarse language and zombie violence, there's a real sweetness to this movie and I caught myself smiling for 90 straight minutes, right into the song choices for the credits. The zombies aren't very formidable given who has to survive them (the U.S. army was scarier to me), but they're really just background to a story about dealing with childhood fears that may have carried into the present, and about parenting and what it means at its core. FAVORITE OF THE WEEK

The Man Who Could Work Miracles is like many H.G. Wells stories (and in this case, he actually worked on the screenplay), just a touch too didactic to really work as a drama. There is a point where, even if I sympathize with his sentiments about humanity, things get bogged down in speeches, philosophy, and so on. But the film still opens on a cracker, with gigantic cosmic beings discussing Earth and the possibility of giving humans god-like power. As an experiment, the less cynical "angel" gives one man wish fulfillment (without impugning free will, well done) to see what happens. What follows is something of an indictment of humanity, but one laced with hope. Thanks to the lead having little imagination, he gets counsel from many (which is part of the didactic mold), so we variably see how absolute power would be used for selfish things and for grandiose selfless projects, but mostly how the forces of social progress are fated to be stymied by a status quo that feeds on inequity. No surprise, the bankers and businessmen and warmongers argue against a utopia where basic need has been eliminated. The Golden Age will just have to wait, but Wells does suggest it WILL come. If the drama is second to the message, the cool 1930s effects do give an extra reason to watch.

For a movie about baseball, 1951's Angels in the Outfield doesn't have a whole lot of baseball in it. Rather, it's about saving a man's soul, and I think it's the better for it (sorry, sports fans). Paul Douglas is a crabby baseball coach with a foul mouth who tends to end arguments with violence; he's made a lot of enemies and karma being a bitch, his team is losing all the games. Then he gets approached by a baseball player turned angel whose team starts helping his players in exchange for getting back on the path of righteousness. We never see these supernatural beings, though they undoubtedly exist in the world of the film, the Miracle on 34th Street-type trial really doesn't have that story's ambiguity for the audience. Janet Leigh is the newspaper columnist who makes a story out of this, and 9-year-old Donna Corcoran is very good as the little orphan girl who alone is able to see the angels. It's a very sweet movie, and some might even say too sweet, but it does have something to say about how the greatest obstacle to reforming is your past self, as forgiveness and trust don't come easy to those with a deservedly bad reputation. By the end, I was completely enamored of this sports fantasy and was rooting for its characters, and for the uncharitable Keenan Wynn to eat crow. I would still say Douglas and Leigh have much too great an age difference to make their romance believable.

Angel on my Shoulder has Paul Muni as a gangster getting killed and going to a phantasmagorical Hollywood hell in the opening minutes, then offered a deal by Claude Rains' brilliant Satan to return to Earth in his physical double's body, a humanitarian judge the Devil wants to ruin. It's basically Bizarro Here Comes Mr. Jordan, but Rains is great whether angel or devil. So a pretty convoluted set-up, but one in which our gangster may or may not get redemption, if only he can resist temptation (in particular, the revenge he feels he owes his double-crossing killer). It's unfortunate then that for most of the picture, Muni's character is one of those dunderheads that just doesn't get the rules of the game. It's a particular bugbear of mine, and I know this is an unusual situation, but he's supposed to be impersonating a judge, and never once attempts to change his dialect, is always speaking to Old Nick who no one else can see, and for the longest time goes "huh?" when someone calls him by his assumed name, always referring to "the judge" in the third person. The film gets away with it by bringing in a psychologist and everyone believing the judge is having a breakdown, or is part of a sting to get the crooks, but it doesn't change the fact that Muni is stupid. The film also fails to stick the landing for me. I'm loathe to spoil even an 80-year-old movie, but let's just say they went for a good ending when a great ending was within reach. Then again, that great ending, while more emotionally satisfying, might have seemed too "easy". I wonder. As is, there are some great scenes (Muni's confrontation with his killer and Rains in general), but I wanted it to be more clever.

Because it's based on a true story (or to be fair, a true biased account of a true story), The Super Cops has a very loose plot, with a rather episodic structure, but what a rollicking entertainment anyway! Though Greenberg and Hantz weren't quite as pure as the movie would have it, this is as close to what real maverick cops would be like, breaking the rules because it's in their nature, but also because the system is broken and it's the only way to get results. There are a lot of clever ruses, but at the same time, they have their share of failures. If it feels real despite the kind of crazy exploitation vibes, it's really because of Ron Leibman's performance. Here's a man who talks a good game - he's definitely the Bugs Bunny of the duo, as much as he is "Batman" - but you can see the fear behind his eyes. He looks unhinged, but it's because he's a trapped animal, his mind racing to find an escape to the dangerous situations he finds--no, PUTS himself in. Leibman went on work on TV a lot, and I remember him as one of those quintessential lawyer / doctor character actors of the small screen, but based on this and Norma Rae alone, I feel like he should have had a much bigger movie career. Very fun stuff.

Black Caesar is essentially the blaxploitation equivalent of a Scorsese gangster film, with the same rise and fall, told like a biopic even when it isn't one, a loose structure informing character, but every sequence not necessarily integral to the plot (heck, there's a bit in the ending that reminded me of The Departed's own). It leans real hard into the antagonists' racism to make sure you root for Fred Williamson's ambitious gangster even though he's a bad dude, but you do (give or take), and the way he climbs the ladder from street kid to self-styled "Caesar" has some satisfying rungs. Great soundtrack too. But it's the final act that really grabbed me. While the movie doesn't really work off Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, it IS a tragedy of betrayal, and the conspirators ARE going to stab Caesar in the back. It's not stabby-stab and done, but rather an extended, desperate chase through the streets while things are going down elsewhere in the organization, then a worthy final confrontation with the movie's main antagonist that harks back to the beginning, well done. The final, bleak ending is quite proper, but was never shown outside of Europe (where they enjoy great tragedy, I guess). Instead, Black Caesar was primed for a quick sequel a darker ending would have obviated.

After the success of Black Caesar, its director Larry Cohen was tasked with making a quick sequel and that's Hell Up in Harlem, which indeed came out later that same year! It's rawer, cheaper, and more sensationalistic, and at times I recognize the Cohen who made the balls-out crazy Q more than I did in the original film. For it to work, characters are established sometimes go out the window (the timid father too easily becomes a crime boss, for example), and the movie plays out as a sometimes insane revenge story, sometimes as James Bond, and in my head canon, I like to think the original film's ending (reprised here excepting the very end) is actually intact, and this is all a fever dream Fred Williamson is having while he dies. Certainly, the action is pushed to extremes that don't really fit the grounded, gritty feel of the original, but it offers a number of memorable moments. It strikes me as a piece of camp at times, which isn't an indictment, it's just a different kind of entertainment. It might all be better if the fight choreography weren't so rushed as well, and the soundtrack, while in the same style, isn't as good. But do we expect from something pieced together last minute before the actors could ask for more money?

Five years before Freaks, Tod Browning made another traveling circus potboiler in The Unknown, and it's a strange and beautiful little piece of twist-ending irony. A young Joan Crawford plays a woman torn between three men - her demanding father, the strongman who loves her, and an armless knife-thrower played with increasing intensity by Lon Chaney who is obsessed with her. He's great, and I thought wow, did he really have that foot dexterity, but no, someone else is playing his legs, putting cigarettes in his mouth and so on... I'm still impressed by the dedication and trickery. Crawford's Nanon has a phobia about being held, so this armless man is just about the only man she can stand. As it turns out, Chaney's Alonzo isn't so 'armless after all, and it gets really weird from there, a carnival tale of jealousy, murder and mutilation like no other. It's kind of what O. Henry might have written after a particularly lurid nightmare, and a great precursor to Freaks.

As a kid, I thought Francis the Talking Mule was a TV show (like Mr. Ed, which I never saw). Maybe I never caught the beginning of one (or noticed the length), maybe I caught several different ones (could there have been a marathon on Nickelodeon one of those Texas summers?), I don't know. From my vestigial memories, it was probably Goes to West Point or Joins the Wacs (or both, or more, they made seven, after all). Watching the first movie, simply called Francis, I have no real memory of it, and though several times, I did catch myself laughing out loud at the absurdity (and the comic timing, it's not just a question of having a ludicrous premise), I still find it too bad that given the World War II setting, the movie is pretty racist towards the Japanese. I don't really want "Japs this, and Japs that" in a trifle meant for kids, you know? Even so, Francis was fun in the way that Herbie films or 50s/60s sitcoms are fun. A lot of that has to do with the human star of (most of) these films, Donald O'Connor whose guileless second lieutenant keeps having to explain where he got his information from, and no one believing his source could be a sarcastic army mule. There's a bit of a spy story as well, but it's far from a puzzler. Bonus points for Patricia Medina's French, which is excellent given she's British, and some will get a thrill from seeing Tony Curtis basically do nothing very early in his career.

Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thieves) isn't quite a neorealist yet in 1944, but he's getting there with The Children Are Watching Us, in particular in his sequences with the boy Pricò. The film is all about his reactions to the adults around him, and they seem so natural as to be non-acting, which is what Italian neorealism was reaching for. Though there's great drama (almost melodrama) in what he's subjected to, namely the infidelity of, and abandonment by, a parent, it seems that the entire adult world is traumatizing for a child. They act like he's not really there, or doesn't understand anyway, but all anyone does in Italy is talk about sex, have long lingering kisses in public, or perhaps it's the image of the Punch and Judy show that stays with you, a puppet couple hitting each other with sticks. Whether Pricò understands the context of all that or not, he registers it. Or at least, we do, and there's an unusual sense of tension for the audience, a ticking clock with a boy's innocence at the end of the fuse. I can't bring myself to dislike either parent whatever their mistakes, because in a way, the whole world is like this. De Sica seems to suggest we're all just the result of various traumas, big and small, an attrition of purity and accumulation of sadness and/or bitterness. It's a sad film, but a truthful one, with good performances, especially that of Luciano De Ambrosis as Pricò.

Though Fred Astaire musicals, with or without Ginger Rogers, always have dodgy sexual politics, Carefree is one of the hardest to watch by modern eyes (at least among the ones that don't have black face). Astaire is the world's least ethical psycho-analysts/hypno-therapists, doing his friend a solid by influencing his girlfriend to marry him, with various crazy complications resulting. It's pretty misogynistic, though I suppose Ginger lets her subconscious get some measure of revenge here and there with ridiculous rampages against the men in her life while under the influence of drugs or hypnosis. I've seen girls get punched out in '30s movies "as a joke" before (Loy and Powell often got violent in that way), but it's the accumulation of offensive elements that makes me dismiss this one like I do, and not want the leads to get together. It's ultimately kind of silly, and some of the dance numbers are good, but no songs feel essential to the canon, and they make us wait just a little too long between numbers for my tastes.

Not gonna pretend, I watched 1939's Fast and Furious just so I could make car jokes. In fact very little car (or fast, or furious) content in this Thin Man rip-off, but I still managed to enjoy it. I'm laying that at the feet of Ann Sothern who is sexy and charming as all get-out as the detective's wife (who herself is more sleuth than slouch in that department), with some high-quality couples flirting and all the best zingers. Even if Franchot Tone necessarily plays the main character, he's always second banana to her. As far as the plot goes, it at least has the virtue of the detective screwing up and his meddling not being appreciated by the local police. After about a half-hour of comedy shenanigans as Tone is signed as a beauty pageant judge against his will, the murder mystery begins, with enough suspects to keep one's interest, but the solution rather lame. There's also a cartoony subplot about a lion tamer, and it loses all the points for featuring a racist caricature (though the white folks kind of have the same caricatured reactions to the lions, I guess). So where was I? Oh yeah, Tone and Sothern should have had a kid because IT'S ABOUT FAMILY! [car spins out]

An early Asian-American-centric film, The Dragon Painter stars Sessue Hayakawa (The Bridge on the River Kwai) as a young, mad artist pining for his bride from another life, which motivates his work. If he later meets his princess and falls in love, what will that mean for his work? It's a Japanese folk tale brought to life, and yes, the tortured artist is a hoary old trope, but I think this is far more about how the artist has trouble wrangling his passion. It's all or nothing. And in love, then it's all about love, screw art. Silent cinema seems perfect for telling these kinds of stories. The flicker of the screen and color filters give them a kind of dreamy quality. The title cards take on a storybook feeling. And like folk tales, they are short, pithy, and not all that concerned with character (in the way that dialog might reveal it). The Dragon Painter is a simple tale, well told. It's only grievous mistake was to cast a Caucasian actor in the role of the patriarch, though at least they didn't push for actual racist make-up.

Basil Dearden isn't a flash director, but he must have had his finger on the pulse of the social change happening in the UK (and elsewhere) in the late '50s/early 60s, judging by the run of movies TCM recently aired in a row. Not knowing they were all from the same director, I DVRed the lot just based on synopses, and almost immediately, got the sense that within well-worn genre pieces, Dearden made films that were very topical. Sapphire, a procedural murder mystery, is particularly precise in its historical placement, on the border between the repressed, racist 50s, and the more liberal 60s, its murder victim a young girl of mixed race who passed for white, and thus might have drawn the ire of members of both communities. Some characters are stuck in the past, holding on to ancient prejudice, while others (including the head investigator played by Nigel Patrick) are more open-minded (and yet, one black character finds liberal whites sanctimonious and patronizing, it's not at all simple). I think one telling moment is when, after the girl's brother tells his story of a white boy making a particularly racist remark when he was young, he's almost run over by a kid on a bike who immediately apologizes and calls him sir. Things are changing, but in the resistance to change lies a murder. Lots of suspects, strong procedural elements, drama... but if you're C.S.I., full trigger warning: They sure didn't know how to handle evidence in the '50s!

The twist in The League of Gentlemen is that it's a heist movie where the robbery is planned and perpetrated by dishonorably discharged servicemen with military precision. It's a real cracker, Basil Dearden bringing his own clockwork precision to the story, efficiently differentiating his post-war Dirty Dozen (well, not quite a dozen) and making us care whether they pull it off and get away with it. The dialog is very witty, and in terms of Dearden's interest in social studies (so to speak), one of the group was cashiered for being gay. Amazingly, it's presented as a fact, we even see him with his partner, but it's never made an issue, nor are those two characters ever played as any kind of caricature (I wonder if the extremely mannered day players who crash one secret meeting at one point are meant to act as contrast). It's a small thing, but in 1960, seems evolved as heck. A lot of tension and humanity, humor even (I love the raid on the military base to get equipment), and no matter how well you plan a heist, things HAVE to go wrong eventually, which is all executed quite well.

Dearden reunites with scriptwriter Janet Green for Victim, which has a lot in common with their previous Sapphire. The crime is different (blackmail) as is the minority subculture (gay men), but we again have an empathetic inspector with a bigoted sergeant, and a large cast of characters whose attitudes, both open and closed-minded, expose through the process of finding the blackmailer. As with Sapphire, it's big on point-making, but doesn't feel particularly preachy. In this case, it's more than just an issue of attitude, since homosexual acts still carry a jail sentence in 1961 Britain. And as with the previous year's The League of Gentlemen, Dearden presents gay characters as real, complex people, not caricatures. It's quite well done, though I do have a problem with one particular red herring that is entirely for the audience's sake and is never even remarked upon by the characters involved in the drama. A massive cheat. I'll say this though, Dearden's London always has the most marvelous fog, giving his city depth, and where in another context it would be dreamy, in his stories it rather speaks to a toxic atmosphere.

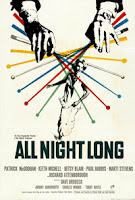

Once you realize All Night Along is Othello set in the singing London jazz scene, you necessarily know what's going to happen, it's just a matter of HOW it will be interpreted. That said, it does hold some surprises and the characters might be differently motivated. The Iago in this story is Patrick McGoohan as a reefer-smoking jazz drummer who wants the wife of a black pianist (mostly for his band), and spends this one evening scheming to get them to break up. McGoohan is terrific as the weasel whose brain is working overtime to keep all the balls in the air, and the script finds fun devices to replace Othello's antiquated ones. It's the kind of thing that really NEEDS to take place in one night, because any more than that, and the various pawns would get wise. But in the haze of drink and smoke, through the highs of watching and participating in a live show, it makes sense. No one has enough time to think. The musicians all play themselves, including Dave Brubeck, probably the most recognizable name on the ticket, and the movie takes frequent breaks to give them the spotlight. Padding? I rather think it's part of the theme here. I once called Iago Shakespeare's great improviser, and jazz is musical improvisation, so this is all of a piece.

Woman of Straw stars Sean Connery as a duplicitous nephew who ropes in a young and supple nurse (Gina Lollobrigida, the best I've seen her) to play nurse to his rich but tyrannical uncle (Ralph Richardson, playing the worst person in the world, if only he were loved), so he can manipulate him into marrying her then extorting money from her when the will is changed and the old, sick man dies. Let's just say monsters breed monsters. The first hour is basically about the mechanics of that plot, and plays as a low-level thriller and melodrama. Things get ramped up considerably in the second, as twist upon twist upon twist renders this a much more interesting story, one that makes you go "aahhh, so that's it" a couple times before the end (and only seldom are we truly ahead of the game). A bit of Hitchcockian macabre in there as well, which is a plus. The more I watched, the more I was invested. And my investment paid off.

There's probably no way around it, Cymbeline's plot is, as they would have said in Elizabethan times, completely bananas. Whether out of frustration or what, I cannot tell, but it feels like Shakespeare is parodying his own brand of theater. He throws as many tropes into the mix as he can - a cross-dressing girl, royal children raised as country bumpkins, turns both tragic and comic, Iago/Othello jealousy traps, a patriotic war, the England of his Histories vs. the Rome of his Caesarean cycle, a wretched queen, a zany buffoon (I could have watched a whole comedy with Cloten and his cross-talking servants), a false death, and more, and to get to the next plot point, he'll dismiss some of these casually, which creates jarring surprises, but also an insane ending that drops reveal on top of reveal like a Scooby-Doo episode where the monster would be unmasked four or five times. Shakespeare is clearly taking the stuffing out of his own style - Hergé did the same with latter-day Tintin stories, the sign of a bored master, perhaps - and one way to play this is as an arch, winking comedy. The 1982 BBC production plays it straight, and even UNDERplays it in a way, and I don't hate that at all. Helen Mirren is a great Imogen (perhaps the one great character in the play), but we get sensitive and intriguing performances from Robert Lindsay, Claire Bloom and Michael Gough as well, quite when a stage version might have gone big. Stronger in set-up than in resolution, Cymbeline is an oddity, its parts stronger than the whole.

National Theatre Live's production of Barber Shop Chronicles has one main setting, a barber shop in London, but creates a tapestry of the Africa's character by transitioning to barbers in various countries on the Continent. Closed captioning was my friend in deciphering certain argots and accents, but what was immediately recognizable was African attitudes and customs, which you tend to pick up when you study and/or work for any length of time in a university setting/town. All audiences will not necessarily get the African politics and such, but the discussions on what it means to be black or an immigrant ring true, many viewpoints are aired, and I really don't mean to make it sound like a social studies lesson, it's also got a tremendous amount of humor (Hammed Animashaun has a particularly funny scene, so funny in fact that he makes the other actors break), heart (I was frequently touched), and music (a mix of African music and hip-hop). Thematically, it tries to connect the big stuff to smaller emotional moments, so that the theft of lands is equated to the perceived theft of a barber shop, or the abuse of Apartheid might feel like that of a violent father who left you nothing but bruises and the wrong generic predispositions. There's a lot going on under the surface, but ultimately, its greatest success is making you care about a large cast of characters who, give or take the main plot, are just shooting the shit (and I guess, trading BARBS) in a variety of barber shops.

Role-playing: Seven players, many of them neophytes, is quite the room, and possibly only manageable with an online solution, but I think we pulled off our first session of Savage Worlds: Rippers. The pilot involved getting funds from a rich suffragette at a museum opening, and the all hell breaking loose when the a necromancer tried and failed to summon an army of the dead in the adjoining cemetery, causing the Natural History Museum's beasties, including a T-Rex skeleton to get animated instead. Leaning into action more than investigation, the point was to give the rules a spin - a refresher course for me, an introduction for the players - with enough repetition to create a semblance of reflexes. One thing to keep an eye on with a lot of players is that they will split up more easily - and story-wise, I feel like the characters act like loners and have yet to bond, there's an arc in that, possibly - so it's important to keep everyone engaged by switching from scene to scene. Savage Worlds' "fast and furious" style was helpful in that sense. The most memorable bit was probably the thief Birdie climbing the T-Rex's spine and sawing off the ties that bound its head to its body. Things starts "falling apart" real fast after that. The bad guy dubbed "Voodouche" by the girls got a cat thrown at him with amusing results, but he left them with an obscure clue that will tie into a larger plot eventually. For now, blank stares. Episode 1: Unnatural History owes a debt of gratitude for inspiration to a Savage World one-sheet written by Dave Blewer and Piotr Korys, though its clear a dinosaur would feature sooner than later because that's my modus operandi.

Also played in our Star Trek Adventures campaign, but I'm just leaving a quick notation here as we're still in the middle of the "pilot" and I can't comment on the story yet. More when the opener resolves and we head into the main premise.

At home: One would be completely within one's rights to ask if, by 2019, the world needed any more zombie films. Well, if Little Monsters is going to be the gauge, I'll gladly let another one squeak in. For the second time in 2019, Lupita Nyong'o stars in a horror film, and like Us, the Australian-made Little Monsters starts out as a simple comedy I would have happily watched to the end without anything horrific happening. Nyong'o is simply resplendent as a kindergarten teacher who fiercely defends her class (their lives but also their innocence) from the monsters, and might also help a man-child (Alexander England) grow up in the process. Josh Gad co-stars as the worst children's show host of all time. The kids are universally terrific and feel real. Despite the coarse language and zombie violence, there's a real sweetness to this movie and I caught myself smiling for 90 straight minutes, right into the song choices for the credits. The zombies aren't very formidable given who has to survive them (the U.S. army was scarier to me), but they're really just background to a story about dealing with childhood fears that may have carried into the present, and about parenting and what it means at its core. FAVORITE OF THE WEEK

The Man Who Could Work Miracles is like many H.G. Wells stories (and in this case, he actually worked on the screenplay), just a touch too didactic to really work as a drama. There is a point where, even if I sympathize with his sentiments about humanity, things get bogged down in speeches, philosophy, and so on. But the film still opens on a cracker, with gigantic cosmic beings discussing Earth and the possibility of giving humans god-like power. As an experiment, the less cynical "angel" gives one man wish fulfillment (without impugning free will, well done) to see what happens. What follows is something of an indictment of humanity, but one laced with hope. Thanks to the lead having little imagination, he gets counsel from many (which is part of the didactic mold), so we variably see how absolute power would be used for selfish things and for grandiose selfless projects, but mostly how the forces of social progress are fated to be stymied by a status quo that feeds on inequity. No surprise, the bankers and businessmen and warmongers argue against a utopia where basic need has been eliminated. The Golden Age will just have to wait, but Wells does suggest it WILL come. If the drama is second to the message, the cool 1930s effects do give an extra reason to watch.

For a movie about baseball, 1951's Angels in the Outfield doesn't have a whole lot of baseball in it. Rather, it's about saving a man's soul, and I think it's the better for it (sorry, sports fans). Paul Douglas is a crabby baseball coach with a foul mouth who tends to end arguments with violence; he's made a lot of enemies and karma being a bitch, his team is losing all the games. Then he gets approached by a baseball player turned angel whose team starts helping his players in exchange for getting back on the path of righteousness. We never see these supernatural beings, though they undoubtedly exist in the world of the film, the Miracle on 34th Street-type trial really doesn't have that story's ambiguity for the audience. Janet Leigh is the newspaper columnist who makes a story out of this, and 9-year-old Donna Corcoran is very good as the little orphan girl who alone is able to see the angels. It's a very sweet movie, and some might even say too sweet, but it does have something to say about how the greatest obstacle to reforming is your past self, as forgiveness and trust don't come easy to those with a deservedly bad reputation. By the end, I was completely enamored of this sports fantasy and was rooting for its characters, and for the uncharitable Keenan Wynn to eat crow. I would still say Douglas and Leigh have much too great an age difference to make their romance believable.

Angel on my Shoulder has Paul Muni as a gangster getting killed and going to a phantasmagorical Hollywood hell in the opening minutes, then offered a deal by Claude Rains' brilliant Satan to return to Earth in his physical double's body, a humanitarian judge the Devil wants to ruin. It's basically Bizarro Here Comes Mr. Jordan, but Rains is great whether angel or devil. So a pretty convoluted set-up, but one in which our gangster may or may not get redemption, if only he can resist temptation (in particular, the revenge he feels he owes his double-crossing killer). It's unfortunate then that for most of the picture, Muni's character is one of those dunderheads that just doesn't get the rules of the game. It's a particular bugbear of mine, and I know this is an unusual situation, but he's supposed to be impersonating a judge, and never once attempts to change his dialect, is always speaking to Old Nick who no one else can see, and for the longest time goes "huh?" when someone calls him by his assumed name, always referring to "the judge" in the third person. The film gets away with it by bringing in a psychologist and everyone believing the judge is having a breakdown, or is part of a sting to get the crooks, but it doesn't change the fact that Muni is stupid. The film also fails to stick the landing for me. I'm loathe to spoil even an 80-year-old movie, but let's just say they went for a good ending when a great ending was within reach. Then again, that great ending, while more emotionally satisfying, might have seemed too "easy". I wonder. As is, there are some great scenes (Muni's confrontation with his killer and Rains in general), but I wanted it to be more clever.

Because it's based on a true story (or to be fair, a true biased account of a true story), The Super Cops has a very loose plot, with a rather episodic structure, but what a rollicking entertainment anyway! Though Greenberg and Hantz weren't quite as pure as the movie would have it, this is as close to what real maverick cops would be like, breaking the rules because it's in their nature, but also because the system is broken and it's the only way to get results. There are a lot of clever ruses, but at the same time, they have their share of failures. If it feels real despite the kind of crazy exploitation vibes, it's really because of Ron Leibman's performance. Here's a man who talks a good game - he's definitely the Bugs Bunny of the duo, as much as he is "Batman" - but you can see the fear behind his eyes. He looks unhinged, but it's because he's a trapped animal, his mind racing to find an escape to the dangerous situations he finds--no, PUTS himself in. Leibman went on work on TV a lot, and I remember him as one of those quintessential lawyer / doctor character actors of the small screen, but based on this and Norma Rae alone, I feel like he should have had a much bigger movie career. Very fun stuff.

Black Caesar is essentially the blaxploitation equivalent of a Scorsese gangster film, with the same rise and fall, told like a biopic even when it isn't one, a loose structure informing character, but every sequence not necessarily integral to the plot (heck, there's a bit in the ending that reminded me of The Departed's own). It leans real hard into the antagonists' racism to make sure you root for Fred Williamson's ambitious gangster even though he's a bad dude, but you do (give or take), and the way he climbs the ladder from street kid to self-styled "Caesar" has some satisfying rungs. Great soundtrack too. But it's the final act that really grabbed me. While the movie doesn't really work off Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, it IS a tragedy of betrayal, and the conspirators ARE going to stab Caesar in the back. It's not stabby-stab and done, but rather an extended, desperate chase through the streets while things are going down elsewhere in the organization, then a worthy final confrontation with the movie's main antagonist that harks back to the beginning, well done. The final, bleak ending is quite proper, but was never shown outside of Europe (where they enjoy great tragedy, I guess). Instead, Black Caesar was primed for a quick sequel a darker ending would have obviated.

After the success of Black Caesar, its director Larry Cohen was tasked with making a quick sequel and that's Hell Up in Harlem, which indeed came out later that same year! It's rawer, cheaper, and more sensationalistic, and at times I recognize the Cohen who made the balls-out crazy Q more than I did in the original film. For it to work, characters are established sometimes go out the window (the timid father too easily becomes a crime boss, for example), and the movie plays out as a sometimes insane revenge story, sometimes as James Bond, and in my head canon, I like to think the original film's ending (reprised here excepting the very end) is actually intact, and this is all a fever dream Fred Williamson is having while he dies. Certainly, the action is pushed to extremes that don't really fit the grounded, gritty feel of the original, but it offers a number of memorable moments. It strikes me as a piece of camp at times, which isn't an indictment, it's just a different kind of entertainment. It might all be better if the fight choreography weren't so rushed as well, and the soundtrack, while in the same style, isn't as good. But do we expect from something pieced together last minute before the actors could ask for more money?

Five years before Freaks, Tod Browning made another traveling circus potboiler in The Unknown, and it's a strange and beautiful little piece of twist-ending irony. A young Joan Crawford plays a woman torn between three men - her demanding father, the strongman who loves her, and an armless knife-thrower played with increasing intensity by Lon Chaney who is obsessed with her. He's great, and I thought wow, did he really have that foot dexterity, but no, someone else is playing his legs, putting cigarettes in his mouth and so on... I'm still impressed by the dedication and trickery. Crawford's Nanon has a phobia about being held, so this armless man is just about the only man she can stand. As it turns out, Chaney's Alonzo isn't so 'armless after all, and it gets really weird from there, a carnival tale of jealousy, murder and mutilation like no other. It's kind of what O. Henry might have written after a particularly lurid nightmare, and a great precursor to Freaks.

As a kid, I thought Francis the Talking Mule was a TV show (like Mr. Ed, which I never saw). Maybe I never caught the beginning of one (or noticed the length), maybe I caught several different ones (could there have been a marathon on Nickelodeon one of those Texas summers?), I don't know. From my vestigial memories, it was probably Goes to West Point or Joins the Wacs (or both, or more, they made seven, after all). Watching the first movie, simply called Francis, I have no real memory of it, and though several times, I did catch myself laughing out loud at the absurdity (and the comic timing, it's not just a question of having a ludicrous premise), I still find it too bad that given the World War II setting, the movie is pretty racist towards the Japanese. I don't really want "Japs this, and Japs that" in a trifle meant for kids, you know? Even so, Francis was fun in the way that Herbie films or 50s/60s sitcoms are fun. A lot of that has to do with the human star of (most of) these films, Donald O'Connor whose guileless second lieutenant keeps having to explain where he got his information from, and no one believing his source could be a sarcastic army mule. There's a bit of a spy story as well, but it's far from a puzzler. Bonus points for Patricia Medina's French, which is excellent given she's British, and some will get a thrill from seeing Tony Curtis basically do nothing very early in his career.

Vittorio De Sica (Bicycle Thieves) isn't quite a neorealist yet in 1944, but he's getting there with The Children Are Watching Us, in particular in his sequences with the boy Pricò. The film is all about his reactions to the adults around him, and they seem so natural as to be non-acting, which is what Italian neorealism was reaching for. Though there's great drama (almost melodrama) in what he's subjected to, namely the infidelity of, and abandonment by, a parent, it seems that the entire adult world is traumatizing for a child. They act like he's not really there, or doesn't understand anyway, but all anyone does in Italy is talk about sex, have long lingering kisses in public, or perhaps it's the image of the Punch and Judy show that stays with you, a puppet couple hitting each other with sticks. Whether Pricò understands the context of all that or not, he registers it. Or at least, we do, and there's an unusual sense of tension for the audience, a ticking clock with a boy's innocence at the end of the fuse. I can't bring myself to dislike either parent whatever their mistakes, because in a way, the whole world is like this. De Sica seems to suggest we're all just the result of various traumas, big and small, an attrition of purity and accumulation of sadness and/or bitterness. It's a sad film, but a truthful one, with good performances, especially that of Luciano De Ambrosis as Pricò.

Though Fred Astaire musicals, with or without Ginger Rogers, always have dodgy sexual politics, Carefree is one of the hardest to watch by modern eyes (at least among the ones that don't have black face). Astaire is the world's least ethical psycho-analysts/hypno-therapists, doing his friend a solid by influencing his girlfriend to marry him, with various crazy complications resulting. It's pretty misogynistic, though I suppose Ginger lets her subconscious get some measure of revenge here and there with ridiculous rampages against the men in her life while under the influence of drugs or hypnosis. I've seen girls get punched out in '30s movies "as a joke" before (Loy and Powell often got violent in that way), but it's the accumulation of offensive elements that makes me dismiss this one like I do, and not want the leads to get together. It's ultimately kind of silly, and some of the dance numbers are good, but no songs feel essential to the canon, and they make us wait just a little too long between numbers for my tastes.

Not gonna pretend, I watched 1939's Fast and Furious just so I could make car jokes. In fact very little car (or fast, or furious) content in this Thin Man rip-off, but I still managed to enjoy it. I'm laying that at the feet of Ann Sothern who is sexy and charming as all get-out as the detective's wife (who herself is more sleuth than slouch in that department), with some high-quality couples flirting and all the best zingers. Even if Franchot Tone necessarily plays the main character, he's always second banana to her. As far as the plot goes, it at least has the virtue of the detective screwing up and his meddling not being appreciated by the local police. After about a half-hour of comedy shenanigans as Tone is signed as a beauty pageant judge against his will, the murder mystery begins, with enough suspects to keep one's interest, but the solution rather lame. There's also a cartoony subplot about a lion tamer, and it loses all the points for featuring a racist caricature (though the white folks kind of have the same caricatured reactions to the lions, I guess). So where was I? Oh yeah, Tone and Sothern should have had a kid because IT'S ABOUT FAMILY! [car spins out]

An early Asian-American-centric film, The Dragon Painter stars Sessue Hayakawa (The Bridge on the River Kwai) as a young, mad artist pining for his bride from another life, which motivates his work. If he later meets his princess and falls in love, what will that mean for his work? It's a Japanese folk tale brought to life, and yes, the tortured artist is a hoary old trope, but I think this is far more about how the artist has trouble wrangling his passion. It's all or nothing. And in love, then it's all about love, screw art. Silent cinema seems perfect for telling these kinds of stories. The flicker of the screen and color filters give them a kind of dreamy quality. The title cards take on a storybook feeling. And like folk tales, they are short, pithy, and not all that concerned with character (in the way that dialog might reveal it). The Dragon Painter is a simple tale, well told. It's only grievous mistake was to cast a Caucasian actor in the role of the patriarch, though at least they didn't push for actual racist make-up.

Basil Dearden isn't a flash director, but he must have had his finger on the pulse of the social change happening in the UK (and elsewhere) in the late '50s/early 60s, judging by the run of movies TCM recently aired in a row. Not knowing they were all from the same director, I DVRed the lot just based on synopses, and almost immediately, got the sense that within well-worn genre pieces, Dearden made films that were very topical. Sapphire, a procedural murder mystery, is particularly precise in its historical placement, on the border between the repressed, racist 50s, and the more liberal 60s, its murder victim a young girl of mixed race who passed for white, and thus might have drawn the ire of members of both communities. Some characters are stuck in the past, holding on to ancient prejudice, while others (including the head investigator played by Nigel Patrick) are more open-minded (and yet, one black character finds liberal whites sanctimonious and patronizing, it's not at all simple). I think one telling moment is when, after the girl's brother tells his story of a white boy making a particularly racist remark when he was young, he's almost run over by a kid on a bike who immediately apologizes and calls him sir. Things are changing, but in the resistance to change lies a murder. Lots of suspects, strong procedural elements, drama... but if you're C.S.I., full trigger warning: They sure didn't know how to handle evidence in the '50s!

The twist in The League of Gentlemen is that it's a heist movie where the robbery is planned and perpetrated by dishonorably discharged servicemen with military precision. It's a real cracker, Basil Dearden bringing his own clockwork precision to the story, efficiently differentiating his post-war Dirty Dozen (well, not quite a dozen) and making us care whether they pull it off and get away with it. The dialog is very witty, and in terms of Dearden's interest in social studies (so to speak), one of the group was cashiered for being gay. Amazingly, it's presented as a fact, we even see him with his partner, but it's never made an issue, nor are those two characters ever played as any kind of caricature (I wonder if the extremely mannered day players who crash one secret meeting at one point are meant to act as contrast). It's a small thing, but in 1960, seems evolved as heck. A lot of tension and humanity, humor even (I love the raid on the military base to get equipment), and no matter how well you plan a heist, things HAVE to go wrong eventually, which is all executed quite well.

Dearden reunites with scriptwriter Janet Green for Victim, which has a lot in common with their previous Sapphire. The crime is different (blackmail) as is the minority subculture (gay men), but we again have an empathetic inspector with a bigoted sergeant, and a large cast of characters whose attitudes, both open and closed-minded, expose through the process of finding the blackmailer. As with Sapphire, it's big on point-making, but doesn't feel particularly preachy. In this case, it's more than just an issue of attitude, since homosexual acts still carry a jail sentence in 1961 Britain. And as with the previous year's The League of Gentlemen, Dearden presents gay characters as real, complex people, not caricatures. It's quite well done, though I do have a problem with one particular red herring that is entirely for the audience's sake and is never even remarked upon by the characters involved in the drama. A massive cheat. I'll say this though, Dearden's London always has the most marvelous fog, giving his city depth, and where in another context it would be dreamy, in his stories it rather speaks to a toxic atmosphere.

Once you realize All Night Along is Othello set in the singing London jazz scene, you necessarily know what's going to happen, it's just a matter of HOW it will be interpreted. That said, it does hold some surprises and the characters might be differently motivated. The Iago in this story is Patrick McGoohan as a reefer-smoking jazz drummer who wants the wife of a black pianist (mostly for his band), and spends this one evening scheming to get them to break up. McGoohan is terrific as the weasel whose brain is working overtime to keep all the balls in the air, and the script finds fun devices to replace Othello's antiquated ones. It's the kind of thing that really NEEDS to take place in one night, because any more than that, and the various pawns would get wise. But in the haze of drink and smoke, through the highs of watching and participating in a live show, it makes sense. No one has enough time to think. The musicians all play themselves, including Dave Brubeck, probably the most recognizable name on the ticket, and the movie takes frequent breaks to give them the spotlight. Padding? I rather think it's part of the theme here. I once called Iago Shakespeare's great improviser, and jazz is musical improvisation, so this is all of a piece.

Woman of Straw stars Sean Connery as a duplicitous nephew who ropes in a young and supple nurse (Gina Lollobrigida, the best I've seen her) to play nurse to his rich but tyrannical uncle (Ralph Richardson, playing the worst person in the world, if only he were loved), so he can manipulate him into marrying her then extorting money from her when the will is changed and the old, sick man dies. Let's just say monsters breed monsters. The first hour is basically about the mechanics of that plot, and plays as a low-level thriller and melodrama. Things get ramped up considerably in the second, as twist upon twist upon twist renders this a much more interesting story, one that makes you go "aahhh, so that's it" a couple times before the end (and only seldom are we truly ahead of the game). A bit of Hitchcockian macabre in there as well, which is a plus. The more I watched, the more I was invested. And my investment paid off.

There's probably no way around it, Cymbeline's plot is, as they would have said in Elizabethan times, completely bananas. Whether out of frustration or what, I cannot tell, but it feels like Shakespeare is parodying his own brand of theater. He throws as many tropes into the mix as he can - a cross-dressing girl, royal children raised as country bumpkins, turns both tragic and comic, Iago/Othello jealousy traps, a patriotic war, the England of his Histories vs. the Rome of his Caesarean cycle, a wretched queen, a zany buffoon (I could have watched a whole comedy with Cloten and his cross-talking servants), a false death, and more, and to get to the next plot point, he'll dismiss some of these casually, which creates jarring surprises, but also an insane ending that drops reveal on top of reveal like a Scooby-Doo episode where the monster would be unmasked four or five times. Shakespeare is clearly taking the stuffing out of his own style - Hergé did the same with latter-day Tintin stories, the sign of a bored master, perhaps - and one way to play this is as an arch, winking comedy. The 1982 BBC production plays it straight, and even UNDERplays it in a way, and I don't hate that at all. Helen Mirren is a great Imogen (perhaps the one great character in the play), but we get sensitive and intriguing performances from Robert Lindsay, Claire Bloom and Michael Gough as well, quite when a stage version might have gone big. Stronger in set-up than in resolution, Cymbeline is an oddity, its parts stronger than the whole.

National Theatre Live's production of Barber Shop Chronicles has one main setting, a barber shop in London, but creates a tapestry of the Africa's character by transitioning to barbers in various countries on the Continent. Closed captioning was my friend in deciphering certain argots and accents, but what was immediately recognizable was African attitudes and customs, which you tend to pick up when you study and/or work for any length of time in a university setting/town. All audiences will not necessarily get the African politics and such, but the discussions on what it means to be black or an immigrant ring true, many viewpoints are aired, and I really don't mean to make it sound like a social studies lesson, it's also got a tremendous amount of humor (Hammed Animashaun has a particularly funny scene, so funny in fact that he makes the other actors break), heart (I was frequently touched), and music (a mix of African music and hip-hop). Thematically, it tries to connect the big stuff to smaller emotional moments, so that the theft of lands is equated to the perceived theft of a barber shop, or the abuse of Apartheid might feel like that of a violent father who left you nothing but bruises and the wrong generic predispositions. There's a lot going on under the surface, but ultimately, its greatest success is making you care about a large cast of characters who, give or take the main plot, are just shooting the shit (and I guess, trading BARBS) in a variety of barber shops.

Role-playing: Seven players, many of them neophytes, is quite the room, and possibly only manageable with an online solution, but I think we pulled off our first session of Savage Worlds: Rippers. The pilot involved getting funds from a rich suffragette at a museum opening, and the all hell breaking loose when the a necromancer tried and failed to summon an army of the dead in the adjoining cemetery, causing the Natural History Museum's beasties, including a T-Rex skeleton to get animated instead. Leaning into action more than investigation, the point was to give the rules a spin - a refresher course for me, an introduction for the players - with enough repetition to create a semblance of reflexes. One thing to keep an eye on with a lot of players is that they will split up more easily - and story-wise, I feel like the characters act like loners and have yet to bond, there's an arc in that, possibly - so it's important to keep everyone engaged by switching from scene to scene. Savage Worlds' "fast and furious" style was helpful in that sense. The most memorable bit was probably the thief Birdie climbing the T-Rex's spine and sawing off the ties that bound its head to its body. Things starts "falling apart" real fast after that. The bad guy dubbed "Voodouche" by the girls got a cat thrown at him with amusing results, but he left them with an obscure clue that will tie into a larger plot eventually. For now, blank stares. Episode 1: Unnatural History owes a debt of gratitude for inspiration to a Savage World one-sheet written by Dave Blewer and Piotr Korys, though its clear a dinosaur would feature sooner than later because that's my modus operandi.

Also played in our Star Trek Adventures campaign, but I'm just leaving a quick notation here as we're still in the middle of the "pilot" and I can't comment on the story yet. More when the opener resolves and we head into the main premise.

Comments