Buys

About 200 pages into the first volume of Marc Cushman's These Are the Voyages, I decided I wanted the set, so I got his books on Star Trek The Original Series Season 2 and 3.

"Accomplishments"

In theaters: There are many sources listed for Shakespeare's Hamlet, a couple of them being Scandinavian in origin, and the closest to the play's events being the legend of Amleth, transmitted to us distorted by a Saxon writer, but allegedly based on an Icelandic poem. Robert Eggers' most straightforward feature, The Northman, tries to show us what that original tale might have been like, reinterpreting Hamlet as a Viking Saga, reverse-engineering the play's key source. Like the play, it is a revenge story, and like the play, its supernatural elements are for the most part ambiguous. Shakespeare's Hamlet isn't invoked - Amleth the Berzerker isn't delaying his action from any kind of psychological trait, he's fated to do so only under certain circumstances. So while knowing the story being told - which I realized pretty early on - does "spoil" the basic plot, its surprises remain in interpretation, some deviating substantially from the play to respect the Saga formula. While not exactly a horror film, it's still Eggers, a master of desaturated cinematography and staged gore. This is in fact a very violent film, but it's so immersive that it feels entirely natural to this well-researched world. Still, I'm sure a lot of people walked out of the theater a little dazed.

At home: I don't know why people insist on drawing over Rosa Salazar (Alita Battle Angel and now Undone) because she's got an incredibly expressive face and should be a big star. The live action to animation style of Undone can't hide that, of course, and though the first episode is played pretty straight, the value of taking the animated route becomes clear as of the second as things take a mind-bending turn. Either Alma has shamanic powers that allow her to travel inside her own timeline, or she's mentally ill, like her grandmother, and hallucinating. A modern exploration of mysticism as perceived in different cultures (including the Westernized idea that seers were actually schizophrenic), the show manages to be funny (Alma especially) and poignant (the second season especially), while exploring existentialist themes AND providing several "time travel missions/mysteries" as Alma tries to fix herself and her family. When I say it's absolutely beautiful, I don't just mean the artwork.

There are a lot of things working against Catherine Tate's new mockumentary series about a women's prison, Hard Cell, one of which is the concept of letting Tate play half a dozen characters. Most are good, but it really takes away from the documentary element, at least, until you get used to it. Another problem is that despite it taking place in a women's prison, it's very much derivative of The Office, with the guv'nor who just wants her people to have fun and be creative (the documentary crew follows a program where the inmates put on a musical), creating all sorts of problems. Yet another is that it goes to body fluid jokes rather fast, and goes after low-hanging fruit like "nobody understands the Welsh inmate's accent", youch. It almost seemed like what made Hard Cell (earning its homophonic name more and more at this point in the review) watchable was that promise that it was just a 6-episode engagement. But it does worm itself into your good graces, with quite a few genuine laughs, and my favorite thing in shows about terrible people, random moments of kindness and grace. And then it chucks it all away by trying to be clever and acting like it's Orange Is the New Black, if not Oz, pulling a last minute tonal shift that may well displease you as it did me.

Before Fleabag, Phoebe Waller-Bridge created and wrote Crashing, which may or may not have always been meant to be a one-season wonder, but it doesn't mean fans aren't still begging for a follow-up. It has that kind of ending that wouldn't be amiss in a movie, but feels like a promise in a series. Anyway, Crashing makes brilliant use of all those disused hospitals Britain seems to have by making it a very strange "apartment complex", where property guardians are thrown together as roommates. Waller-Bridge herself plays a spoiler who has maintained a will they, won't they relationship with one of the housemates since they were kids, showing up the year of his wedding to a comically jealous girlfriend. Other house mates include a sex addict who has to accept he's bisexual, and a French artist who wants to paint (and bed) a lumpy, depressed divorcé. It's amazing how much stuff there is in only six episodes, including a lot of weirdness played straight. As with Fleabag, it's funny but drives towards tragedy, and people behaving badly is a matter of course. It's more straightforwardly told than Fleabag, but no less absorbing.

Big is one of those movies you think you've seen, but maybe you haven't. The giant piano scene has been parodied countless times, and the premise adapted into vehicles for other actors who want to let out their inner child. I thought *I'd* seen it, but no, I don't think I had until this week. Or maybe it's what my friend Marty said about it: Today, adults are much more likely to own toys, read comics and play games, so young Tom Hanks doesn't seem that out of place in today's world, even in the world of executives. And that makes it familiar not because we've seen it, but because we've lived it. It would be weird to say a film is dated exactly because it predicts the future, but that's because what it's about is out of focus. It almost touches on something with the jerkwad character who is more childish in attitude than Josh, then almost on something else by asserting that these toy executives are out of touch with children and their own childhood, but doesn't complete the pass on either theme. I like the existential danger Josh faces as he becomes more and more integrated into the world of adults and starts to become one in negative ways (too busy for others, stressed, etc.), but the catalyst is the objectionable romance between him (13 going on 30) and an adult woman, a relationship that at first played for laughs, eventually becomes physical. VERY physical. Try not to cringe through the second half of the movie if you can. Because it's a comedy, no one - not the worried parents who think their child was kidnapped for 6 weeks, not the woman who is made aware that she molested a child, and not Josh - will be traumatized or negatively impacted by these events, and so it goes. But you have to wonder who such a script was written FOR. If kids who wish they were adults, then why the sex stuff? If adults who wish they were kids again, then why the sex stuff? It's a good thing young, comedy-era Tom Hanks is so endearing, because it really wouldn't work as well as it does even with those problems.

Blaxploitation meets art house in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, a historically and culturally significant film, but no easy watch, opening as it does with a disturbing pedophilic sequence where young Sweetback has simulated sex with a grown woman (you've been warned). Director and star Melvin Van Peebles was evidently inspired by the French New Wave in his approach to editing, but there are so many interesting effects that if I were a film maker, I'd want to perpetually "quote" this movie. It's certainly rough, guerilla film making, with a lot of non-actors, and the plot is thin and secondary to creating transgressive, hallucinatory vignettes. Van Peebles is working in the same mode as John Waters, but with righteous anger rather than a comic approach. The key is in the title. This is jazz cinema, a violent, sex-fueled ton poem set to a great groove and not to be understood in the usual narrative terms. It would be true to say that I admire more than like it.

The Friday Foster comic strip was already gone by the time Pam Grier played her in 1975, but it explains why the film seems to be one in a series, with its own theme song, opening sequence, and pre-existing supporting cast. It's both the film's strength and its weakness. On the one hand, it seems very confident as a result, and while Friday isn't Grier's most badass role, the character's lightness means it's perhaps one of her most beautiful. Unfortunately, it also does feel like it's a random episode from some television show (albeit in a universe where TV shows have foul language, harsh violence, and women gratuitously taking their shirts off any time they can) with its convoluted crime plot and recurring gags. Setting part of the story in Washington D.C. gives it some production value, but if this one continues to interest, it's because it has one of the most recognizable casts in blaxploitation history: Yephet Kotto (Live and Let Die) is a handsome P.I.; Eartha Kitt camps it up in a role that's just half an inch from her Catwoman; Scatman Crothers is a dirty old reverend; and young Carl Weathers shows up as the main assassin! Oh and Jim Backus (Gilligan's Island's millionaire) is in it too, as is the ubiquitous Jason Bernard (you'll know him when you see him). It all amounts to a bit of fun starring the grande dame of blaxploitation.

In J.D.'s Revenge, a perfectly nice man is sporadically possessed by a 1940s gangster, and it becomes an intense Jekyll and Hyde situation well played by Glynn Turman, but what's really interesting is the conversation he has with his best friend around the middle of the film. After abusing his girlfriend but remembering none of it, he confides in his buddy who tells him it's okay because women want to be put in their place, etc. The movie has something to say about toxic masculinity, with Ike as a the kinder, gentler modern man, and J.D. as the brutal throwback. But of course, his buddy is a 1970s contemporary so that attitude hasn't disappeared. Speaking of toxic, do I get it right that J.D. banged his own niece in Isaac's body? Calling Dr. Freud, yeech! Louis Gossett Jr. gives an energetic supporting performance as a preacher, a role that doesn't go where formula says it should, but I have to disagree with his assessment that J.D. is a tool for God's justice. He's much too nasty for that. Sometimes evil spirits do a righteous thing, you know?

George Lattimer (Top of the Heap's writer, director and star Christopher St. John) is a cop who gets no respect at work, at home, or on the street, and he's going to crack. This a movie that uses blaxploitation tropes to covertly deliver a piece of literary naturalism where, despite the character's ambitions, he can't get anywhere. What makes it less heavy than the later (but possibly indebted) Bad Lieutenant is George's surreal day dreams of being the first black man on the moon. But this streak of afrofuturism, while initially a contrast to his real life, may well just be ironic. All exploitation aside, Top of the Heap is a strong portrait of the cognitive dissonance that comes with protecting a system that puts you and people like you down, and the depressing pointlessness of trying to change things from the inside - not that George ever claims he's trying to... he's already a disappointed man on the edge by the time we meet him.

A lot of blaxploitation films act like they're installments of TV shows, with titles based on the lead character, theme music to match, television-type supporting casts, and a crime plot of the week or two. Or in the case of Truck Turner, at least three. Isaac Hayes provides his own music this time, playing the title bounty hunter who hits like a mack truck (and everyone knows it). A lot of cool details, like a girlfriend who's always in and out of jail, a very good cat actor (to the point that I thought he was Hayes' own), and a surprise appearance by Nichelle Nichols as a foul-mouthed Madame. The action is pretty standard for this kind of thing, but my problems are with the structure. Directorially, it's all over the place. We keep switching villains as if it really were a bunch of episodes smashed together, and the tone jumps around accordingly. The first half of the movie seems to dial the exploitation elements way down, but the second half is violent to the point of cruelty. Yaphet Kotto's last scene has a really cool art house touch I wish had been more prevalent throughout, and then going after the final boss feels almost like an afterthought. So while Truck Turner is fun and lively, I can't quite recommend its story.

Owing less to Bonnie & Clyde than it does Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (especally in terms of music and editing), Thomasine & Bushrod is a late-era, revisionist western about a bank robbing couple heading for tragedy, though a substantial part of me wanted a more triumphant ending. Max Julien (The Mack) wrote the Bushrod part for himself, but despite the after-dark name, he's a very chill fellow. Too chill for his own good. It's Vonetta McGee as the fiery, volatile Thomasine who makes the biggest impression - at least, when Glynn Turman doesn't swoop in to steal the show as a Jamaican outlaw - absolutely destroying every scene she's in and deserves her character getting top billing. You'd think the 1911 setting would justify a lot more racism than is habitually shown in blaxploitation films, but the white characters are impressed by these Robin Hoods, and even the villains are unusually restrained in terms of language. That makes T&B a bit of a charmer, and we can forgive its loose, lackadaisical plot.

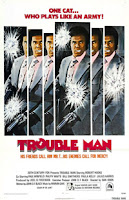

Written by Star Trek's original script editor, John D.F. Black, Trouble Man stars Robert Hooks as "Mr. T" who HAS to be an inspiration for THE Mr. T given that his persona as a community hero seems pulled directly from this. People might also recognize Luke Cage as played on TV, though Mr. T's only power is his immense cool, and the massive reputation that comes with it. He's a kind of fixer for the black community in his corner of Los Angeles, getting in and out of trouble with ease, and in this particular story, the most trouble he's ever gotten. Caught between two criminal gangs (with the uncooperative police squeezing in yet another direction), he could end up framed, or dead. But the man is so slick, he never loses his cool (he may fake it for intimidation purposes though) and it's that cool that makes the flick so fun. Mr. T isn't the only recognizable name either - Julius Harris plays a "Mr. Big" a year before his character works for a Mr. Big in Live and Let Die. Just how influential was this thing?!

It's the Hip-hop Generation vs. the Soul Generation in Original Gangstas, pitting old blaxploitation stars against modern-day gangbangers, and Larry Cohen (I think my favorite B-movie director) is using the two possible soundtracks to great effect. Expendables before there were Expendables, only better, the movie has Fred Williamson, Jim Brown, Pam Grier (who is poignantly emotional as the grieving mother who will help avenge her child), and to a lesser extent, Richard Roundtree and Ron O'Neal, team up with a community under threat. It's just fun to see all these actors back in action, in a rough and tumble format that's akin to their 70s work, if not exactly as cool. But then they're older, more grounded, if just as resolute. It's bit slow to get to the big action, but again, it feels like it's just how older, wiser heroes roll, contrasting with the impulsive, raging gang members they're up against. I think it works a lot better than their imitators' effort.

Books: The Pirandello play most people have heard of, Six Characters in Search of an Author has a family of fictional characters (apparently from a novel Pirandello abandoned, just to add another layer) crashing a play's rehearsal and begging to have their drama written and staged. Except they really don't, because directors and actors ruin everything with their changes and "play-acting". This is what the author is known for. Philosophically taking the piss out of the very form he's writing for by deconstructing the hyper-reality of theater and literature. On the one hand, he exposes the artifice - the collapsed scenes, the writerly structures, the stage conceits - and asks how we can accept this "reality". How can actors claim they "live" it? How can audiences find any kind of "truth" in it? A lot of the lively fun of the play is to hear the characters attack the translation from live to page to stage (Reality vs. Novel vs. Play?). On the other, Pirandello continues to examine the theme of identity, and whether a fictional character - designed to be someone, whole and fixed - is more real than an actual personal - who can, after all, be no one, and is ever-changing, unfinished and unfixed. When one of the characters asks the Manager (director) who he thinks he is, he teasingly reminds us that this "real person" on stage is just as much a character being played. Now let's throw that question to each and every audience member... For me, it all ends too abruptly and needs a cleverer button, but the play is nevertheless filled with meaning and interest. I wish I could see it staged, because nuances of acting might make or break it.

About 200 pages into the first volume of Marc Cushman's These Are the Voyages, I decided I wanted the set, so I got his books on Star Trek The Original Series Season 2 and 3.

"Accomplishments"

In theaters: There are many sources listed for Shakespeare's Hamlet, a couple of them being Scandinavian in origin, and the closest to the play's events being the legend of Amleth, transmitted to us distorted by a Saxon writer, but allegedly based on an Icelandic poem. Robert Eggers' most straightforward feature, The Northman, tries to show us what that original tale might have been like, reinterpreting Hamlet as a Viking Saga, reverse-engineering the play's key source. Like the play, it is a revenge story, and like the play, its supernatural elements are for the most part ambiguous. Shakespeare's Hamlet isn't invoked - Amleth the Berzerker isn't delaying his action from any kind of psychological trait, he's fated to do so only under certain circumstances. So while knowing the story being told - which I realized pretty early on - does "spoil" the basic plot, its surprises remain in interpretation, some deviating substantially from the play to respect the Saga formula. While not exactly a horror film, it's still Eggers, a master of desaturated cinematography and staged gore. This is in fact a very violent film, but it's so immersive that it feels entirely natural to this well-researched world. Still, I'm sure a lot of people walked out of the theater a little dazed.

At home: I don't know why people insist on drawing over Rosa Salazar (Alita Battle Angel and now Undone) because she's got an incredibly expressive face and should be a big star. The live action to animation style of Undone can't hide that, of course, and though the first episode is played pretty straight, the value of taking the animated route becomes clear as of the second as things take a mind-bending turn. Either Alma has shamanic powers that allow her to travel inside her own timeline, or she's mentally ill, like her grandmother, and hallucinating. A modern exploration of mysticism as perceived in different cultures (including the Westernized idea that seers were actually schizophrenic), the show manages to be funny (Alma especially) and poignant (the second season especially), while exploring existentialist themes AND providing several "time travel missions/mysteries" as Alma tries to fix herself and her family. When I say it's absolutely beautiful, I don't just mean the artwork.

There are a lot of things working against Catherine Tate's new mockumentary series about a women's prison, Hard Cell, one of which is the concept of letting Tate play half a dozen characters. Most are good, but it really takes away from the documentary element, at least, until you get used to it. Another problem is that despite it taking place in a women's prison, it's very much derivative of The Office, with the guv'nor who just wants her people to have fun and be creative (the documentary crew follows a program where the inmates put on a musical), creating all sorts of problems. Yet another is that it goes to body fluid jokes rather fast, and goes after low-hanging fruit like "nobody understands the Welsh inmate's accent", youch. It almost seemed like what made Hard Cell (earning its homophonic name more and more at this point in the review) watchable was that promise that it was just a 6-episode engagement. But it does worm itself into your good graces, with quite a few genuine laughs, and my favorite thing in shows about terrible people, random moments of kindness and grace. And then it chucks it all away by trying to be clever and acting like it's Orange Is the New Black, if not Oz, pulling a last minute tonal shift that may well displease you as it did me.

Before Fleabag, Phoebe Waller-Bridge created and wrote Crashing, which may or may not have always been meant to be a one-season wonder, but it doesn't mean fans aren't still begging for a follow-up. It has that kind of ending that wouldn't be amiss in a movie, but feels like a promise in a series. Anyway, Crashing makes brilliant use of all those disused hospitals Britain seems to have by making it a very strange "apartment complex", where property guardians are thrown together as roommates. Waller-Bridge herself plays a spoiler who has maintained a will they, won't they relationship with one of the housemates since they were kids, showing up the year of his wedding to a comically jealous girlfriend. Other house mates include a sex addict who has to accept he's bisexual, and a French artist who wants to paint (and bed) a lumpy, depressed divorcé. It's amazing how much stuff there is in only six episodes, including a lot of weirdness played straight. As with Fleabag, it's funny but drives towards tragedy, and people behaving badly is a matter of course. It's more straightforwardly told than Fleabag, but no less absorbing.

Big is one of those movies you think you've seen, but maybe you haven't. The giant piano scene has been parodied countless times, and the premise adapted into vehicles for other actors who want to let out their inner child. I thought *I'd* seen it, but no, I don't think I had until this week. Or maybe it's what my friend Marty said about it: Today, adults are much more likely to own toys, read comics and play games, so young Tom Hanks doesn't seem that out of place in today's world, even in the world of executives. And that makes it familiar not because we've seen it, but because we've lived it. It would be weird to say a film is dated exactly because it predicts the future, but that's because what it's about is out of focus. It almost touches on something with the jerkwad character who is more childish in attitude than Josh, then almost on something else by asserting that these toy executives are out of touch with children and their own childhood, but doesn't complete the pass on either theme. I like the existential danger Josh faces as he becomes more and more integrated into the world of adults and starts to become one in negative ways (too busy for others, stressed, etc.), but the catalyst is the objectionable romance between him (13 going on 30) and an adult woman, a relationship that at first played for laughs, eventually becomes physical. VERY physical. Try not to cringe through the second half of the movie if you can. Because it's a comedy, no one - not the worried parents who think their child was kidnapped for 6 weeks, not the woman who is made aware that she molested a child, and not Josh - will be traumatized or negatively impacted by these events, and so it goes. But you have to wonder who such a script was written FOR. If kids who wish they were adults, then why the sex stuff? If adults who wish they were kids again, then why the sex stuff? It's a good thing young, comedy-era Tom Hanks is so endearing, because it really wouldn't work as well as it does even with those problems.

Blaxploitation meets art house in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, a historically and culturally significant film, but no easy watch, opening as it does with a disturbing pedophilic sequence where young Sweetback has simulated sex with a grown woman (you've been warned). Director and star Melvin Van Peebles was evidently inspired by the French New Wave in his approach to editing, but there are so many interesting effects that if I were a film maker, I'd want to perpetually "quote" this movie. It's certainly rough, guerilla film making, with a lot of non-actors, and the plot is thin and secondary to creating transgressive, hallucinatory vignettes. Van Peebles is working in the same mode as John Waters, but with righteous anger rather than a comic approach. The key is in the title. This is jazz cinema, a violent, sex-fueled ton poem set to a great groove and not to be understood in the usual narrative terms. It would be true to say that I admire more than like it.

The Friday Foster comic strip was already gone by the time Pam Grier played her in 1975, but it explains why the film seems to be one in a series, with its own theme song, opening sequence, and pre-existing supporting cast. It's both the film's strength and its weakness. On the one hand, it seems very confident as a result, and while Friday isn't Grier's most badass role, the character's lightness means it's perhaps one of her most beautiful. Unfortunately, it also does feel like it's a random episode from some television show (albeit in a universe where TV shows have foul language, harsh violence, and women gratuitously taking their shirts off any time they can) with its convoluted crime plot and recurring gags. Setting part of the story in Washington D.C. gives it some production value, but if this one continues to interest, it's because it has one of the most recognizable casts in blaxploitation history: Yephet Kotto (Live and Let Die) is a handsome P.I.; Eartha Kitt camps it up in a role that's just half an inch from her Catwoman; Scatman Crothers is a dirty old reverend; and young Carl Weathers shows up as the main assassin! Oh and Jim Backus (Gilligan's Island's millionaire) is in it too, as is the ubiquitous Jason Bernard (you'll know him when you see him). It all amounts to a bit of fun starring the grande dame of blaxploitation.

In J.D.'s Revenge, a perfectly nice man is sporadically possessed by a 1940s gangster, and it becomes an intense Jekyll and Hyde situation well played by Glynn Turman, but what's really interesting is the conversation he has with his best friend around the middle of the film. After abusing his girlfriend but remembering none of it, he confides in his buddy who tells him it's okay because women want to be put in their place, etc. The movie has something to say about toxic masculinity, with Ike as a the kinder, gentler modern man, and J.D. as the brutal throwback. But of course, his buddy is a 1970s contemporary so that attitude hasn't disappeared. Speaking of toxic, do I get it right that J.D. banged his own niece in Isaac's body? Calling Dr. Freud, yeech! Louis Gossett Jr. gives an energetic supporting performance as a preacher, a role that doesn't go where formula says it should, but I have to disagree with his assessment that J.D. is a tool for God's justice. He's much too nasty for that. Sometimes evil spirits do a righteous thing, you know?

George Lattimer (Top of the Heap's writer, director and star Christopher St. John) is a cop who gets no respect at work, at home, or on the street, and he's going to crack. This a movie that uses blaxploitation tropes to covertly deliver a piece of literary naturalism where, despite the character's ambitions, he can't get anywhere. What makes it less heavy than the later (but possibly indebted) Bad Lieutenant is George's surreal day dreams of being the first black man on the moon. But this streak of afrofuturism, while initially a contrast to his real life, may well just be ironic. All exploitation aside, Top of the Heap is a strong portrait of the cognitive dissonance that comes with protecting a system that puts you and people like you down, and the depressing pointlessness of trying to change things from the inside - not that George ever claims he's trying to... he's already a disappointed man on the edge by the time we meet him.

A lot of blaxploitation films act like they're installments of TV shows, with titles based on the lead character, theme music to match, television-type supporting casts, and a crime plot of the week or two. Or in the case of Truck Turner, at least three. Isaac Hayes provides his own music this time, playing the title bounty hunter who hits like a mack truck (and everyone knows it). A lot of cool details, like a girlfriend who's always in and out of jail, a very good cat actor (to the point that I thought he was Hayes' own), and a surprise appearance by Nichelle Nichols as a foul-mouthed Madame. The action is pretty standard for this kind of thing, but my problems are with the structure. Directorially, it's all over the place. We keep switching villains as if it really were a bunch of episodes smashed together, and the tone jumps around accordingly. The first half of the movie seems to dial the exploitation elements way down, but the second half is violent to the point of cruelty. Yaphet Kotto's last scene has a really cool art house touch I wish had been more prevalent throughout, and then going after the final boss feels almost like an afterthought. So while Truck Turner is fun and lively, I can't quite recommend its story.

Owing less to Bonnie & Clyde than it does Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (especally in terms of music and editing), Thomasine & Bushrod is a late-era, revisionist western about a bank robbing couple heading for tragedy, though a substantial part of me wanted a more triumphant ending. Max Julien (The Mack) wrote the Bushrod part for himself, but despite the after-dark name, he's a very chill fellow. Too chill for his own good. It's Vonetta McGee as the fiery, volatile Thomasine who makes the biggest impression - at least, when Glynn Turman doesn't swoop in to steal the show as a Jamaican outlaw - absolutely destroying every scene she's in and deserves her character getting top billing. You'd think the 1911 setting would justify a lot more racism than is habitually shown in blaxploitation films, but the white characters are impressed by these Robin Hoods, and even the villains are unusually restrained in terms of language. That makes T&B a bit of a charmer, and we can forgive its loose, lackadaisical plot.

Written by Star Trek's original script editor, John D.F. Black, Trouble Man stars Robert Hooks as "Mr. T" who HAS to be an inspiration for THE Mr. T given that his persona as a community hero seems pulled directly from this. People might also recognize Luke Cage as played on TV, though Mr. T's only power is his immense cool, and the massive reputation that comes with it. He's a kind of fixer for the black community in his corner of Los Angeles, getting in and out of trouble with ease, and in this particular story, the most trouble he's ever gotten. Caught between two criminal gangs (with the uncooperative police squeezing in yet another direction), he could end up framed, or dead. But the man is so slick, he never loses his cool (he may fake it for intimidation purposes though) and it's that cool that makes the flick so fun. Mr. T isn't the only recognizable name either - Julius Harris plays a "Mr. Big" a year before his character works for a Mr. Big in Live and Let Die. Just how influential was this thing?!

It's the Hip-hop Generation vs. the Soul Generation in Original Gangstas, pitting old blaxploitation stars against modern-day gangbangers, and Larry Cohen (I think my favorite B-movie director) is using the two possible soundtracks to great effect. Expendables before there were Expendables, only better, the movie has Fred Williamson, Jim Brown, Pam Grier (who is poignantly emotional as the grieving mother who will help avenge her child), and to a lesser extent, Richard Roundtree and Ron O'Neal, team up with a community under threat. It's just fun to see all these actors back in action, in a rough and tumble format that's akin to their 70s work, if not exactly as cool. But then they're older, more grounded, if just as resolute. It's bit slow to get to the big action, but again, it feels like it's just how older, wiser heroes roll, contrasting with the impulsive, raging gang members they're up against. I think it works a lot better than their imitators' effort.

Books: The Pirandello play most people have heard of, Six Characters in Search of an Author has a family of fictional characters (apparently from a novel Pirandello abandoned, just to add another layer) crashing a play's rehearsal and begging to have their drama written and staged. Except they really don't, because directors and actors ruin everything with their changes and "play-acting". This is what the author is known for. Philosophically taking the piss out of the very form he's writing for by deconstructing the hyper-reality of theater and literature. On the one hand, he exposes the artifice - the collapsed scenes, the writerly structures, the stage conceits - and asks how we can accept this "reality". How can actors claim they "live" it? How can audiences find any kind of "truth" in it? A lot of the lively fun of the play is to hear the characters attack the translation from live to page to stage (Reality vs. Novel vs. Play?). On the other, Pirandello continues to examine the theme of identity, and whether a fictional character - designed to be someone, whole and fixed - is more real than an actual personal - who can, after all, be no one, and is ever-changing, unfinished and unfixed. When one of the characters asks the Manager (director) who he thinks he is, he teasingly reminds us that this "real person" on stage is just as much a character being played. Now let's throw that question to each and every audience member... For me, it all ends too abruptly and needs a cleverer button, but the play is nevertheless filled with meaning and interest. I wish I could see it staged, because nuances of acting might make or break it.

Comments