"Accomplishments"

In theaters: The comedy whodunit See How They Run is a lot of fun. Set in and around a long-running Agatha Christie play in 1950s London, and the movie production waiting in the wings, it's full of Easter Eggs referencing Agatha's works and other whodunits, and a kind of self-aware humor that delightfully comments on this type of story. While Sam Rockwell is the detective in charge - a Clouseau-esque drunkard who nevertheless gets on with it - the heart and soul of the piece is the constable played by Saoirse Ronan. She is HILARIOUS as the over-eager policewoman, making for a great comedy double act you wouldn't mind seeing in further mysteries. (If Knives Out can do it...) Director Tom George doesn't have a lot of credits to his name, but this particular effort looks like it's taking a page from Wes Anderson (and perhaps some of the actors involved help give this impression). Not too much as to be a rip-off, but enough to lend a designed theatricality that works with the film's themes. We genuinely chuckled throughout.

At home: The thing that attracts you to The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot - its title - is also its biggest weakness. It creates expectations in terms of tone - crazy B-movie à la Kung Fury, but it's not that at all, much more poignant - and it gives away the game in terms of plot (or plots, one a flashback, the other current day). One to throw on your list of movies in which Sam Elliott sits at a bar, this is a dark, reflective story about the assassin who took out Hitler, an act that made him jaded, disabused and haunted by the memories of what he lost as a result. It's about the pointlessness of killing - did Hitler's dream die with him? ask yourself that - and when he's pulled out of retirement to track the plague-infested missing link, it only seems like it's coming out of left field (imagine if the title didn't telegraph it), but is a thematically correct trip back in time to kill humanity before it spawns. Whether they deserve it or not, there's a moral ugliness to killing that can't be denied, though our protagonist nevertheless goes through a kind of catharsis as a result. Elliott is damn good in this, damn, damn good, and worth the price of admission. And you know me, I always give bonus points for crazy elements, which this movie definitely has.

|

In 1991, Graham Greene gets an Oscar nomination for supporting White Messiah Extraordinaire Kevin Costner in 1990's Dances with Wolves. Playing an unhinged Native Canadian who kidnaps and tortures (mostly psychologically) a couple of would-be White Messiahs in Clearcut that year seems like a weird - but appreciated! - revenge. I really like what this does for the subgenre. White audiences are programmed to side with the lawyer fighting for indigenous land rights against the cartoonish mill owner (Battlestar Galactica's Michael Hogan actually brings a fun, dark humor to what could have been a thankless role), and just as programmed to think of Greene's character as the villain. He's the neighbor or babysitter you shouldn't have pissed off in other thrillers. But it's all a big take-down of the White Messiah complex and the lawyer is entirely ineffectual and Greene is essentially exposing his liberal outrage as, not false exactly, I'm gonna use the word "professional". Does he care because he actually does, or is it just his job to care, and does he confuse the two? When push comes to shove (and it does), which culture is our lawyer going to respect? Flip it and make Greene's character the hero, without changing him in any way, and you'd think he was justified, but because the POV character is someone else, you're forced to ask more questions. This is more of a talking piece (especially the ending) than your casual thriller. Nothing is actually... clearcut.

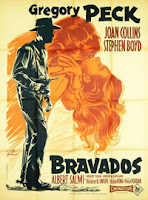

In The Bravados, Gregory Peck walks into a small town holding their first ever hanging to see the four condemned men twitch at the end of a rope for the terrible wrong he believes they've done him. Of course, they'll escape and he'll be forced to track them down. That's the gist of this better-than-most western that on the one hand, doesn't always follow formula, and on the other, turns out to be a dark moral fable about one's reasons and justifications for murder. That final act is excellent, and Henry Silva really shines as one of the fugitives (though hey, always nice to see Lee Van Cleef too). Joan Collins is so young in this as to be unrecognizable, but - and Trek fans will understand when I mean by this - she has a very distinctive way of saying "Jim", our hero's name. Her voice is unmistakable, even when affecting a kind of American accent. As this is a moral tale, there's a shockingly big Catholic church in the middle of this small town - it sort of took me out of it at different points, but I suppose it works in the context of this being so near the Mexican border. Could be land taken from the Spanish. Then again, I have trouble figuring out where this is supposed to be in terms of geography (it was all shot in Mexico, so actual American landscapes need not apply).

In Accident, Joeph Losey presents us with a car crash. A philosophy professor races out of his house, sees it's two young people he knows, takes the survivor into his house and doesn't tell the police about her. Who are they? Why were they racing dangerously towards his home? Why would he cover for the girl? We're sent back in time through his memories, pitched as moments that heighten his particular concerns - aging, inadequacy, vitality, lust as a means to forget the first and restore/prove the last - often textured, detailed and subtle in their meanings - but to call this a "puzzle film" or even any kind of who/whydunit is probably incorrect. There's no big mystery, just a different kind of structure to hang the tale on, and provide psychological context for the man's actions AFTER the accident (we're deep in HIS point of view and other people are often a mystery, as in life). Though Dirk Bogarde is the star, young Michael York plays an important role, and Delphine Seyrig, though only really in one scene, is always a delight.

The Father of Surrealist Cinema, Luis Buñuel, sends us down the merry road of Christianity take-downs in The Milky Way (which is sometimes called the Path of St-James, a pilgrimage two tramps are more or less making in the film). Though largely just thematically-linked vignettes criss-crossing the "path", often seeming like parables, their dialog taken directly from Scripture and theology texts, it's a delight in the way it mixes religious iconography, various historical time frames, surrealism (I love the bit where one character hears another's imagination), and sarcastic exploration of Christianity's hypocrisies. If there's a big take-away, it's that Christianity isn't, nor has never been monolithic, and Catholicism especially (which Latin Europe and its colonies is still saddled with) takes as given things that are not in the Bible whatsoever, and that even biblical literalists ignore half of everything and misinterpret the other half. By juxtaposing different points in religious history, Buñuel highlights the kind of Frankenstein's Monster organized religion really is, a mess of contradictions, strange add-ons, and dated dogma. May anathema be upon me, but I thought it was a lot of fun.

From the first shot of Baxter, Vera Baxter (which is on the poster), Marguerite Duras is painting with her camera. I don't know if she's referencing actual paintings (that first one, certainly) or just evoking portrait, still life and landscape generally, but this IS a portrait. The portrait of a woman, but as the title subtly hints, her disintegrating marriage in particular. Duras isolates characters in their own frames, very seldom going to two-shots, and often letting conversations play out on shots empty of people. Vera is melancholy, not even finding joy in her current affair, which she describes severally to different people. She calls herself a liar, but Delphine Seyrig's helpful stranger later brings us a possible key - that this isn't necessarily about Vera, but about all women who have felt abandoned by men throughout history, and perhaps have had affairs not out of lust, as men have, but out of loneliness. The subject matter is heavily contrasted by some kind of Peruvian party music piping in from no place in particular, celebrating Vera's emancipation even as she laments it. An incredibly interesting picture that might serve as companion to Akerman's Jeanne Dielman (which probably comes to mind because of Seyrig's participation).

In Daughters of Darkness (better French title, "Les lèvres rouges" - The Red Lips), newlyweds find themselves alone with a pair of vampiric ladies in a Dutch hotel during the off-season, a film that knows you know all the vampire tropes and therefore never feels the need to explain itself on that score. The gory moments come late, but have an unhinged, almost Argento-like quality, but that's neither here nor there. It's a about seduction and the allure of the dark side. That's been part of the formula at least since Dracula, you might say, but instead of a male Count who draws women in, it's a Countess (Delphine Seyrig so... yow) doing so (still young women). On the menu, possibly, is the young woman du jour's toxic, sadistic husband, so she might already primed to give in to Seyrig's glamorous succubus. Hm, vampiric existence as edging towards danger just to feel alive... that also applies to the violent husband, who has a secret himself that is unfortunately never revealed. What WAS the whole story with "Mother"? Almost seems like the movie was heading in one direction and abruptly turned left at the third act.

Delphine Seyrig gets behind the camera for Sois belle et tais-toi! (Be Pretty and Shut Up!), a series of interviews with actresses about what it means to BE a woman in the industry - Hollywood's (there's a surprising number of English speakers who have to be voiced over, then subtitle, which is confusing to the bilingual mind) and French-speaking Europe's - at what might well be the nadir for quality roles for women - shot in 1975, made available in 1981. While female powerhouses ruled the early decades of cinema (on screen, if rarely behind the scenes), and there's more diversity today (which has attracted a lot of overt misogyny), from the late 60s to the early 90s, cinema was oppressively masculine. This is where we catch up with these performers - case in point, Cindy Williams is in here decrying the fact that she's never played a warm relationship with another woman, well before Laverne & Shirley. Their consensus, severally collected, is that the movie and TV business is about bringing male fantasies to life, and not until women take control of the means (producing and directing in particular) can women's roles improve. I was particularly touched by the jobbers stuck in small or television-guesting roles that are all the same and have nothing to offer them as artists. You'd have to be a sucker for punishment to become an actor - I've always believed that - but several of Seyrig's interviewees admit they only fell into it because it was one of the very few ways for a woman to leave home, go abroad, etc. and wouldn't have done it otherwise. So though things have moved on in certain ways (and not in others, and probably very little at the low end of production quality), this remains an important reflection today.

Comments